I can’t imagine what it’s like to design, construct and supervise a world leading structure, receive wide praise and recognition, and have it fail causing dozens of deaths 19 months later. Thomas Bouch knew exactly what that was like.

I learned about the Tay Bridge disaster when I was very young. I grew up in Fife, and to get to Dundee we went north by train crossing the River Tay estuary on the 2.75 mile long Tay Bridge.

Aged less than seven, I looked out the train window and down to the water, and asked ‘Why are there stone blocks in the water alongside our bridge?’

My mum explained, ‘Those large blocks held up the first bridge. But it fell down.’ That wasn’t an encouraging answer, but I wanted to know more. And I’m still interested today.

In this blog I’ll tell the story of what happened to the original Tay Bridge. This is a different kind of blog to most. It’s longer, because the story can’t be told properly without detail. And why things went so terribly wrong is a lesson or warning for all of us.

But if it’s too much, you’re about to be given a shortcut.

Construction

I’m about to provide considerable detail about the construction of the bridge, including failings that likely caused its downfall. Not everyone will have time or will wish to read this. If so, pick up the story again in the section headed ‘Collapse’.

The River Tay flows into the North Sea just east of Dundee. Its estuary is wide with fast flowing currents and strong winds. To bridge across the river near its mouth would be a massive engineering feat.

Proposals were drawn up in 1854, but nothing done. In the 1860s, however, two rail companies rivalled each other for the route to the north east. The key to success was building a bridge over the River Tay. The North British Railway Company got approval to do that, and they appointed a noted civil engineer called Thomas Bouch. He was 49, and already experienced with major railway projects in both Scotland and England. The whole contract – design, construction and ongoing maintenance – went to him. In 1871 work began.

From earliest days Bouch’s design was criticised. The bridge would be only single track so traffic capacity would be low. The centre section needed to be built high above water to allow ships to pass underneath. Bouch’s tall and slim design appeared to lack stability.

Problems soon emerged once construction started. Bouch’s design specified piers (on which the bridge would rest) of solid masonry and brickwork. But 15 piers out from the south side, the borers who dug into the next part of the river bed found the underlying material insufficient to hold the weight of solid piers. They would shift or collapse. So Bouch redesigned these piers to be lighter and wider. Above water level, instead of masonry there would be slender cast-iron columns. He made another change: originally the centre of the bridge was to have fourteen 61-metre spans, but finally he settled on thirteen 65.5-metre spans (the gap between piers).

Three other issues are worth mentioning.

The foundry Bouch built a foundry at Wormit, immediately beside the south end of the bridge. That was a good idea – hardly any distance was involved in transporting the iron. But numerous reports described low-quality iron emerging from that foundry – inconsistent in shape and inconsistent in quality.

The height necessary to allow vessels to pass For most of the bridge, girders ran under the rails. But those low girders reduced the height of the bridge, far too low for ships to pass underneath. So, in the centre section the girders were constructed alongside and above the railway track, allowing trains to pass through a tunnel-like gap between the metalwork. Hence that section got the name of the High Girders.

Wind pressure Modern standards for wind resistance did not exist in Bouch’s time, but engineers were well aware of the issue. He took advice about wind pressure. French and American engineers had already adopted 40-50 pounds per square foot for wind loading (and if a Tay Bridge was being built today that would be the design requirement). But the lowest recommendation Bouch was given was 10 pounds per square foot. He took that, believing that wind intensity at that level would not force the bolts upwards that secured the columns to their piers.

Throughout the project there was pressure on Bouch from his employers to work as fast as possible, and to keep costs down. The bridge took six years to build. The materials used included:

- 10,000,000 bricks

- 2,000,000 rivets

- 87,000 cubic feet of timber

- 15,000 casks of cement

Six hundred men were employed during the construction; 20 of them died in accidents. The bridge cost was £300,000 which was not a high amount at the time. It equates to approximately £20,000,000 today, though modern bridges cost many times that sum.

The bridge was more than two miles long. Some records say it was the longest bridge in the world; others that it was the longest iron bridge, or the longest rail bridge. It impressed many. General Ulysses Grant, who led the Union Armies to victory in the American Civil War, visited the construction in 1877 while he was President of the United States.

The Tay Bridge was opened officially on 31st May, 1878, with great celebrations. Directors were taken over the bridge in a special train. Passenger traffic commenced the next day. Profits for the rail company soared.

In June 1879 Queen Victoria crossed the bridge as she journeyed south from Balmoral Castle. A few days later Thomas Bouch was knighted by the Queen at Windsor Castle.

Collapse

It’s now Sunday evening of the 28th December, 1879. Winter nights in Scotland are cold. This night there are also howling winds. On a naval training ship moored at Dundee, the wind speed is measured as gusting to Force 10/11.

On the south side of the River Tay a train approaches the bridge. There’s the locomotive, its tender, five passenger carriages and a luggage van. The last passengers have boarded at St Fort Station and are likely locked in, thought of as a safety measure. At Wormit, on the southern edge of the river, the train slows to 3 or 4 mph as a safety baton is passed over. At 7.13 pm the train moves on to the Tay Bridge.

It’s only 19 months since the bridge was opened. Thousands of passengers have crossed, including Queen Victoria. But not on a night like this. Gale force winds sweep down the Tay river valley. Some say no train should be using the bridge over the estuary on such a night. But this train does.

From the south signal box, through wind and rain an observer watches the tail lamps of the train as it moves on to the bridge. When it reaches 200 yards he sees sparks at the wheels. Probably the wind is pushing the wheel flanges against the edge of the rail. Those sparks fly for almost three minutes. Now the train is in the High Girders central section. The observer later described what happened next: ‘there was a sudden bright flash of light, and in an instant there was total darkness, the tail lamps of the train, the sparks and the flash of light all … disappearing at the same instant’.

He tells the signalman, who until now has been busy with other duties. Neither of them can see anything through the darkness. To be sure all is well, the signalman uses a cable phone (which was attached to the bridge) to call the signal box at the north end. He can’t get through. They don’t know what to think.

Officials on the Dundee side expect the train to arrive. When it doesn’t, they wonder if it ever left the south bank. Still they wait, but see and hear nothing. Finally two men volunteer to go out on the bridge. Perhaps the train is stuck. Or something worse. What they’re doing is immensely risky. Many times they are almost blown off the bridge. One stops, but the other reaches the point where the high girder section starts. It’s gone. And the train is gone. Holding on to save his life, he peers out over the raging river, realising the bridge ahead, the train, the crew and the passengers have all plunged into the water.

At first light ships search the Tay. They find no survivors. To this day different numbers are given for how many died, but most agree it was around 75.

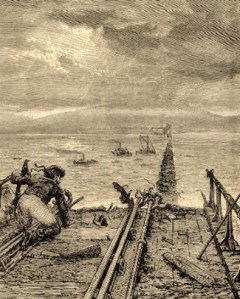

As news spreads there is nation-wide shock. Newspapers publish sensational drawings of the train plunging off the tracks into the Tay. The engineering world is stunned.

When the storm is over, divers go down to the wreck. They find the locomotive and its carriages still inside the girders. It had all come down together. Only 46 bodies are recovered.

One of the most remarkable feats of engineering now lies at the bottom of the river it spanned.

Consequences

After a tragedy the two immediate questions are ‘How did it happen?’ and ‘Who should we blame?’ Answers came soon.

An official Court of Inquiry was set up immediately with three commissioners. The disaster occurred on 28th December, 1879, and evidence was taken as early as 3rd January, 1880, just six days later.

They gathered eye witness testimony from people who had seen something from shore, and appointed senior engineers to investigate the wrecked sections and the remainder of the bridge. Others considered the design and construction methods. Months were spent gathering and examining expert reports and interviewing key people.

None was more key than Sir Thomas Bouch, who argued that derailment and collision with the girders explained the tragedy. His view was considered to have little supporting evidence.

The Court of Inquiry’s report was published a few months later and presented to both the Commons and the Lords in the Houses of Parliament. All points were not agreed in the report. But there was reasonable unanimity in serious criticisms of the design, the poor ironwork produced by the Wormit foundry causing some parts to fail when under heavy load, mistakes made during construction, inadequate maintenance and remedial measures. And a failure to create a structure able to withstand the strength of winds which could occur in the Tay estuary.

Here are two damning comments in the official report: *

‘…can there be any doubt that, what caused the overthrow of the bridge, was the pressure of the wind, acting upon a structure badly built, and badly maintained.’ (p.41)

‘The conclusion then, to which we have come, is that this bridge was badly designed, badly constructed, and badly maintained, and that its downfall was due to inherent defects in the structure, which must sooner or later have brought it down. For these defects both in the design, the construction, and the maintenance, Sir Thomas Bouch is, in our opinion, mainly to blame. For the faults of design he is entirely responsible.’ (p.44)

Bouch was broken by the Inquiry’s findings. He became a recluse and died of ‘stress’ in October 1880, four months after the report was published. He was 58.

Down all the years, arguments persist about what caused the bridge to fall. Bouch continues to be blamed, though perhaps a little less severely than by the official inquiry. But if the ‘buck stops at the top’, he was, unquestionably, at the top with this project.

Here’s what I think happened. Almost all the factors mentioned earlier had their part to play. Parts failed that with proper workmanship and maintenance should have stayed strong. But, fatally, when the locomotive and all its carriages entered the high girders, they created what one website calls ‘a solid broadside resistance to the gale, which was blowing full on to them’. A yacht is moved forcefully when the flat of the sail is presented to the wind. On that night, at the highest point of the bridge, that train plus the high girders were a heavy flat surface facing directly towards a powerful wind. It was too much. The whole central section was pushed sideways, tilting the girders over, snapping the cast-iron columns, and driving the high girders and the train into the Tay.**

Conclusions

From the story of the Tay Bridge disaster, I have three short conclusions for our lives today.

Too much dependence on one person is risky

I wouldn’t like to have been Thomas Bouch, even at the start of the bridge project. He was a brilliant civil engineer, but there are 20 or perhaps 50 different specialised areas involved in a major construction and he didn’t and couldn’t have knowledge and skills for all these areas.

When I led churches, the mission agency, the seminary, I was uncomfortable when too much about our work depended on one person. Sometimes I asked: ‘If you were run over by a bus, who could do your job?’ If no-one could, we were vulnerable.

Some people like feeling indispensable. But for an organisation, that’s not strength; it’s weakness.

A great vision isn’t enough. Implementation really matters

No-one had built a two-mile long iron bridge before. Bouch’s vision was great. But he was pressurised on time scale and on cost. Corners were cut, too much didn’t get designed well, built well, inspected well, maintained well. Bouch’s big ideas were really good, but many things during and just after construction were lacking. Hindsight is always 20/20, but it seems it was only a matter of time before the bridge failed.

Some of us look back to when we were given a great opportunity. A new job. A wonderful spouse. Good health. University entrance. A rare skill. And we didn’t make the most of it. We didn’t study, or develop our abilities, or got distracted on to far less important things. It’s one thing to get a great opportunity. It’s another to fulfil our potential with that opportunity. Implementation really matters.

What we do is always tested

The 28th of December, 1879 – the night of the terrible storm – was the ultimate test for the Tay Bridge. And it fell. When tested, it failed.

The sobering truth is that every life faces tests.

- Politicians know re-election time is coming when what they’ve done will be scrutinised and voted on

- Students will face assignments and exams, and what they know will be assessed

- Workers will have appraisals. Their performance will be evaluated.

- Relationships will go through hard times, a test of how strongly they hold together

Knowing that there will be times of testing should motivate us to prepare and live ready to face them.

My Aunt Milla drove really badly. Her top speed on all roads was 25 mph. She couldn’t parallel park on a deserted street. She was poor at judging traffic at junctions, and solved that by just going straight through. It was terrifying to be her passenger. Question: how did she ever pass a test when she drove like that? Answer: she didn’t pass a test. She’d begun to drive before there were any tests, so she simply applied for a licence and was given one. But because she’d never prepared for a test, she was forever a dreadful and dangerous driver.

We’re living well when we’re prepared for whatever test will come. Some tests are the ordinary challenges of this life. From my Christian perspective, there’s also the ultimate test of standing before God, and accounting for what we’ve done with all that’s been entrusted to us.

May we be ready for that, the greatest of tests, and all the others along the way.

—————————-

A special thanks and acknowledgment. The images in this blog are used with the permission of ‘Libraries, Leisure and Culture Dundee’. Their website is full of information, and their staff wonderfully helpful.

* The official report can be found at: https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/documents/BoT_TayInquiry1880.pdf

** I’m grateful for this explanation from the Wonders of World Engineering website: https://wondersofworldengineering.com/tay-bridges.html

Thank you for persevering with this blog. If you’ve found it interesting or useful, pass it on to family and friends. You can use the ‘Share’ button, or just point them to www.occasionallywise.com

Three extra details:

The locomotive that plunged into the Tay was recovered, restored and put back in service. Its new nickname was ‘The Diver’.

Parts of the old bridge are still in use today – suitable girders were incorporated into the structure of the replacement Tay Rail Bridge.

The new bridge is twin track, opened in 1887 without any official ceremony.