Welcome to the third and last section of the Christmas Quiz I used during a recent church service.

Many have followed the earlier parts of this quiz. In the last few days there have been readers from 20 nations, including the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Finland, Laos, Moldova, Venezuela, Vietnam, Japan, Hong Kong, USA and the UK. I am delighted people from all these countries and cultures find something useful here.

If this is your first encounter with the Christmas Quiz, you would enjoy beginning with the first two parts. Here’s where to find them:

As well as the quizzes, you’ll discover how each one has three parts: 1) the quiz; 2) the answers; 3) a personal reflection. The reflections were the challenge I brought to the church congregation, and it would be wrong to omit them here.

Lastly before we start, avid readers of Occasionally Wise may have an advantage for this third quiz, because I wrote about some of the same subjects in Christmas Miscellany (https://occasionallywise.com/2024/12/21/christmas-miscellany/). But, this time, I’ve added a lot of extra information. You’ll enjoy what you read here!

Part 1 Christmas celebrations

Q1 What percentage of people in the UK say they will attend church on Christmas Day?

- 6%

- 16%

- 26%

Q2 Looking back in history, who was most influential in promoting the Christmas tree tradition?

- Ancient pagans, such as Druids

- Martin Luther, around 1536

- Queen Charlotte, German wife of King George III, in the late 1700s and early 1800s

- Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert, from the 1840s

Q3 In 1848 Cecil Frances Alexander wrote ‘Once in Royal David’s City’ as a children’s hymn. Which of these other hymns did she write?

- ‘There is a green hill far away’.

- ‘All things bright and beautiful’.

- ‘Away in a manger’

Q4 In Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, people think little elf-like creatures bring presents on Christmas Eve. What food do children leave out for them to eat – to thank them and help them on their way?

- Sausages

- Porridge

- Cakes

Q5 Mince pies were being enjoyed 800 years ago. Back then what were their main ingredients?

- Meat

- Dried fruit

- Spices

Q6 In the UK, how many mince pies are sold in the run-up to Christmas?

- 80,000

- 800,000

- 800,000,000

Q7 Mince pies have had various shapes over the years. Back in medieval times what shape were they?

- Round

- Star

- Rectangular

Part 2 Answers to Quiz 3 questions

Question 1 asks what percentage of people surveyed in the UK say they will attend church on Christmas Day. Maybe the most important words in the question are “say they will attend”. That tells you the survey was done before Christmas. If the survey had been done after Christmas and asked how many had actually gone to church on Christmas Day, the numbers would surely have been smaller. Intentions do not always lead to actions. True for all of us.

The right answer – from that survey – is 16%. That may not seem many, but 16% is close to 1 in 6 of the population. I live in the UK and I’m sure that 1 in 6 of those who live near me do not attend church on any day, including Christmas Day! Maybe my affluent neighbours in Oxfordshire are sucked into feasting and present-giving/receiving at Christmas.

The survey not only compared planned attendances at church between the USA, UK, and Germany, but also how many intended to go to the pub. Two things may have skewed answers to the pub question. First, maybe other countries are different, but many pubs in the UK do not open on Christmas Day. Second, there is something wonderful about being in church at Christmas but nothing particularly special happens in the pub on Christmas Day. And nipping off to the pub when you’ve got famly duties at home could have serious consequences!

Nevertheless, it’s interesting to note from the survey that in all three countries, church wins over pub. At least that’s what they told the pollsters.

Question 2 asks who was most influential in promoting the Christmas tree tradition. Once again it’s important to think carefully about the wording of the question.

First, let’s take pagans and Druids of ancient times out of the picture. They did gather branches of evergreen trees to ward off evil spirits. Why those branches? Precisely because they were evergreen – they never seemed to die which, they believed, meant those who gathered them would also never die. But pagans are not behind our Christmas tree tradition. They weren’t interested in promoting their traditions, and Christians were never much interested in adopting them.

What about Martin Luther, the reformer of the church in the 1500s? The story goes that he was walking home on a cold, clear winter night, and felt overwhelmed by the remarkable display of bright stars overhead. He erected an evergreen tree in his home, and fastened lighted candles to its branches, intending to recapture something of the beauty he had seen in the sky outside. The result was Impressive, and Germany did develop an early custom with similar trees, but Luther’s tree did not inspire a world-wide movement.

Now, if the question had asked who first introduced the Christmas tree tradition to Britain, then Queen Charlotte would be a great answer. She grew up in the German duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, where it was customary at Christmas to lay out a single yew branch, to which were attached wax tapers that could be lit. Presents would be placed under the branch.

Charlotte came to Britain in 1761 to marry King George. She soon established the yew branch tradition in her new home, but that was only for her family with some court members joining them to sing carols. But the tradition got a significant upgrade in 1800 when Queen Charlotte set up a Christmas tree at Queen’s Lodge, Windsor, and that is reckoned to be the first ever Christmas tree in the UK. Charlotte decorated the tree with tinsel, glass, ornaments and fruits, and brought local children in for a party. John Watkins attended the party and later wrote a biography of Queen Charlotte in which he described the branches of the tree from which “hung bunches of sweetmeats, almonds and raisins in papers, fruits and toys, most tastefully arranged; the whole illuminated by small wax candles. After the company had walked round and admired the tree, each child obtained a portion of the sweets it bore, together with a toy, and then all returned home quite delighted.”[1] I am sure they did.

Erecting Christmas trees began to catch on among the nobility, and in some of the colonies. But by far the biggest boost for the tradition came several decades later. Note that the question asked who was most influential in promoting the Christmas tree tradition, and the correct answer is Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert.

Victoria and Albert had both enjoyed Christmas trees during their childhood. They married in 1840, and Christmas trees soon appeared around Windsor Castle. Then Prince Albert did something in 1848 which massively spread the tradition. He allowed a front cover painting to appear in The Illustrated London News showing the main tree covered in decorations and surrounded by the Royal Family.[2] Other publications – in the UK and many other countries, especially the United States – reproduced the painting and followed up on the story. The publicity had a massive influence on Christmas customs, and by 1860 almost every well-off family in Britain and Ireland had a Christmas tree in their home. Royal fever had done its work.

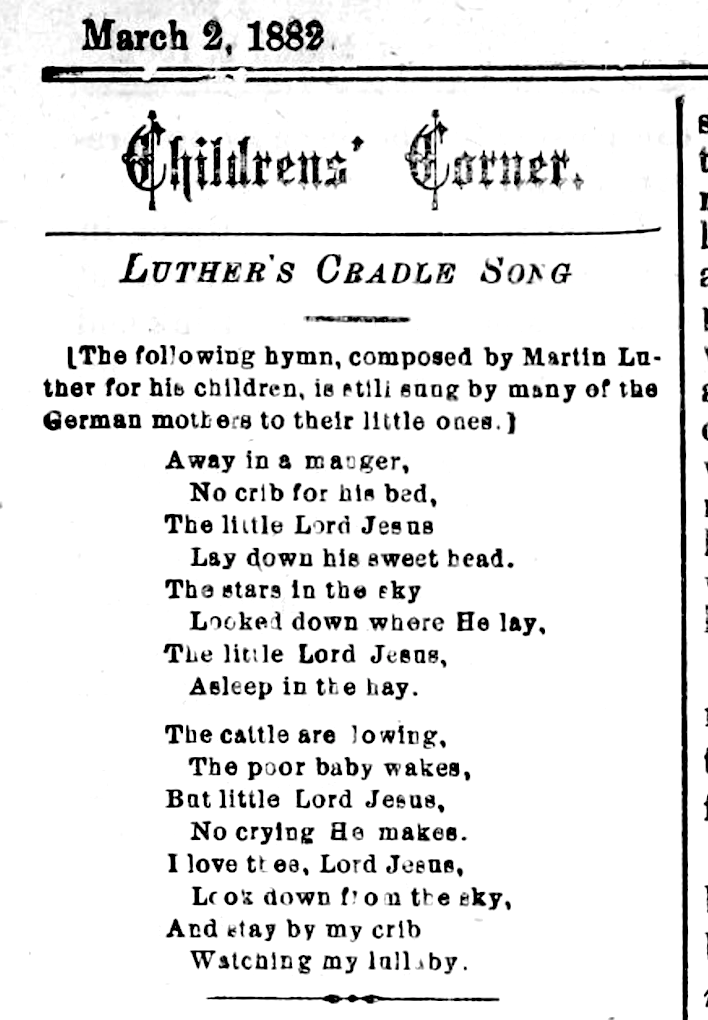

Question 3 asks about hymns possibly written by Cecil Frances Alexander in addition to her famous carol ‘Once in Royal David’s City’. I listed three. When I posed this question to the church congregation, a large number chose a wrong answer: ‘Away in a manger’. Though that carol is hugely popular, its authorship is unknown. The first two verses appeared in various American publications in the 1880s, typically attributing the hymn to Martin Luther. The third verse which begins ‘Be near me, Lord Jesus’ first appeared in 1892 in Gabriel’s Vineyard Songs. But, even without the extra stanza, what was being called “Luther’s Cradle Song” was being sung widely in America. There is no evidence of a version dating from Martin Luther’s time, but attributing the hymn to him probably helped spread its popularity. Luther and his wife Katie had 6 children as well as raising 8 orphaned nieces and nephews. It must have been difficult to lull them all to sleep, but it wasn’t done by singing ‘Away in a Manger’.

So, which of the other two hymns were written by Cecil Frances Alexander? The correct answer is that she’s the author of both ‘There is a green hill far away’ and ‘All things bright and beautiful’. These two, and ‘Once in Royal David’s City’ first appeared in Alexander’s Hymns for Little Children in1848. The simple style and structure of all three will have been a major reason they became so popular.

Cecil married an Anglican clergyman who later became Bishop of Derry and Archbishop of Armagh, and spent much of her time caring for poor, sick or disadvantaged people, especially during the Irish potato famine (1845-1852). She has been criticised, however, for the original third verse of ‘All things bright and beautiful’ because it acknowledges the separation of classes: ‘The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, God made them high or lowly, And ordered their estate.’ That verse is almost never sung today.

Question 4 pondered what treats are left out in some Scandinavian countries for elf-like creatures who bring presents at Christmas. A good number of votes in church went for sausages, even more for cakes, and only a few for porridge. But the correct answer is porridge. Apparently Scandinavian children think healthy food will speed elves on their way through a long night of leaving presents. There must be very healthy children and elves in Scandinavia.

Question 5 asks about the main ingredients of mince pies when first made and eaten 800 years ago. The options were Meat, Dried fruit, or Spices. The right answer is all three. And each part of the mince pie was there for a reason:

- meat (mostly lamb or mutton) was simple food because it represented the shepherds

- dried fruit (raisins, prunes and figs) because they were an affordable alternative to sugar to sweeten the mince pie

- spices (cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg), were, along with the fruit, expensive items as they were imported from the Middle East, but their cost symbolised the lavish gifts of the wise men.

In those medieval times mince pies had 13 ingredients. Why 13? Because that was equal in number to Jesus and his 12 disciples.

Question 6 was about how many mince pies are sold in the UK during the run-up to Christmas. I offered alternatives of 80 thousand, 800 thousand or 800 million. The correct answer is a staggering 800 million. Of course that’s only how many are sold. It does not include all those baked at home, nor those bought or made at other times of the year.

To know how many mince pies per person are eaten each Christmas in the UK, you can’t just divide the population into 800 million. Why not? Because some people don’t like mince pies so never eat any. Then there are babies who can’t or shouldn’t eat mince pies, and young children who don’t like them now but may later in life. However, rough estimates suggest that those who like mince pies will eat between 15 and 19 per person at Christmas. Add to that all the other fattening foods they’ll consume, and it’s no mystery why many of us put on weight over Christmas!

Question 7 explains that mince pies have had various shapes, but asks what shape they were in medieval times. Were they round, star or rectangular? The correct answer is rectangular because they were baked in large dishes with that shape – and consequently often called ‘coffins’. But bakers of ancient times also recognised rectangular dishes were similar to a manger, and, with that in mind, many topped their pies with a pastry baby Jesus figure. Personally I can’t imagine cutting or biting into a pie decorated with Jesus. The round shape of mince pies – common today – dates only from the Reformation in the 1500s.

Part 3 Reflection

Christians tend to frown on the extravagance and excess of fringe activities which accompany Christmas – parties, decorations, gifts, over-indulgent meals, perhaps even the mince pies. Surely these things are not what Christmas is all about?

No, they are not. But there is nothing wrong with Christmas celebrations providing the fringe things do not become the main thing. Jesus went to a wedding reception with plenty of food and wine. He didn’t refuse to attend, objecting that food, drink and dancing were not what marriage is about. He joined others in celebrating what the main event meant, a couple pledging their love and lives to each other. Likewise, as long as we recognise that the main thing about Christmas is God coming into this world to save us, we can celebrate.

But we go wrong if we allow Christmas to stand alone. Christmas belongs with Easter, because Easter is the fulfilment of what began at Christmas. You need both to understand what God was doing by coming into this world. I’ll explain.

I grew up only nine miles from St Andrews, the ancient ‘home of golf’. When I was aged about 13, I entered the prestigious Eden Boys’ Golf Championship at St. Andrews. It was played on the Eden Golf Course, but those who qualified in the early rounds would play later rounds on the famous Old Course. I was playing well. I knew I’d qualify.

I arrived at the course, carrying my second hand clubs in an old canvas golf bag, and wearing the same clothes as I did when playing football with friends. But one boy, maybe aged 15, was dressed immaculately. He had a proper golf hat, proper golf slacks, proper golf sweater, proper golf shoes. And he’d brought brand new clubs in a brand new bag which contained brand new balls. He even had a caddie to carry his clubs and guide him round the course. He stepped onto the first tee with a swagger. His backswing was immaculate and the downswing looked good too. But clearly it wasn’t, because although the lad hit the ball hard, he sliced his shot way off to the right where it disappeared over the course boundary to land among old railway sheds. His caddie tossed the boy another brand new ball. He drove, and off to the right and out of bounds that one went too. So did number 3. Number 4 did not, only because he topped the ball and it ran a mere 100 yards down the fairway. As he walked away, I saw no swagger, just a crestfallen figure who knew he’d lost any chance of winning on the first hole. I wasn’t going to do that.

I didn’t. My chances didn’t disappear on the first hole, just on almost every hole after that. From hole 2 on, my drives and fairway shots went all over the place and my putts kept missing the hole. I was well over par after nine holes. My Dad had come to watch me. He was a very good player with a low single figure handicap. That day he was at the side of every fairway, and I knew he would be silently cheering me on. But, as I messed up yet another shot, I was thinking ‘Today what I need is not my Dad watching me; I need him to come over here and play the shots for me.’ Which, of course he couldn’t. I didn’t qualify.

Christmas is not about God watching us as we mess up our lives. It is about God coming from heaven to earth to save us. We mess up – so much of what we think and do is out of bounds – but God did not sit in heaven, wringing his hands and feeling sorry or angry about our lives. He came, not to watch us but to save us. That began with his birth into this world at Christmas, and was completed when he died and rose again at Easter.

God – ruler, judge over all – stepped down to be with sinful men and women, and then take the penalty on the cross for their sins. He died in our place. The angel who told Joseph to take Mary as his wife said: “She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins” (Matthew 1:21). To save us is why he came. That is why Christmas matters so much. I am all for celebrating Christmas. It’s a wonderful, joyous time. The Lord has come. All people on earth should receive their king. Watching from a distance would not have been enough. He came right alongside to save us, and that’s what makes Christmas so special.

[1] Quotation from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_of_Mecklenburg-Strelitz

[2] By 1848 the couple had six children and they are shown in the painting: Victoria (1840), Albert Edward (1841), Alice (1843), Alfred (1844), Helena (1846), and their newest arrival, Princess Louise, born in March 1848. Eventually there were nine children, five daughters, four sons. Their last child – Princess Beatrice – was born in 1857. She died in 1944, having long outlived not only her mother but all her siblings.