My wife, Alison, was planting bulbs around a family grave in my home town. I wandered off, reading the words on headstones. One made me stop and stare. I had never seen a grave stone inscribed like this one.

Three things made it different from all others. Two of the three were truly remarkable.

First, though the headstone was not unusually large, there were more family names on that stone than I would have thought possible. Several generations were being memorialised.

Second, very strangely, the last name listed was someone not yet dead. The person who’d had all the family names inscribed on the headstone had added his own. His name and date of birth were there after which there was simply a space, presumably to be filled eventually with the date of his death.

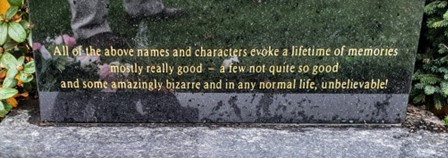

Third, and most peculiar of all, was the inscription right at the foot. I had never seen anything like it on any grave stone anywhere, so I took a photograph.

The wording may not be readable, so here it is:

All of the above names and characters evoke a lifetime of memories / mostly really good – a few not quite so good / and some amazingly bizarre and in any normal life, unbelievable!

Gravestones usually have tender words, kind sentiments praising the life of the deceased. This inscription wasn’t unkind; just the most honest I’ve ever seen.

The truth is that all of us – or, at least, most of us – belong to odd families. When Alison studied health science, including the sociology of health, her lecturer said most people wonder why they’re the only one to struggle with health issues, while the truth is that everyone has health problems. And, likewise, we wonder why our family is so odd compared to others, but actually almost every family has its share of mad, bad, sad and some glad individuals.

It might be the eccentric and extrovert uncle who embarrasses everyone at weddings with his off-key singing or crazy dancing, so dreadful the rest of the family pretend he’s not related to them. Or a brother who’s recently re-joined the family after several years of being accommodated by the government because he dealt in drugs. Or the sister who has been married and divorced so many times that everyone is terrified they’ll use the wrong name for her latest partner. Or the father who abused his daughters. No-one who knows what happened ever mentions his name. Or the niece who has been weak and ill almost all her life. Or the cousin who has changed jobs repeatedly and been spectacularly unsuccessful every time. Or another brother and his wife who lost their only child, killed by a drunk driver. And sometimes, one or more who have found happiness in relationships, success in career, and comfort and hope in their beliefs.

I can’t think of any family who has the whole package I’ve just described. But I also can’t think of any family without a substantial mix of stresses and struggles. Is it the norm to have a happy extended family with everyone friends and no serious problems? Absolutely not.

One of the most memorable speeches of Queen Elizabeth, who died in 2022, was given 30 years earlier when she described 1992 as an annus horribilis, literally a ‘horrible year’. What especially made it so horrible were family troubles:

- February: The estrangement between (then) Prince Charles and Princess Diana became all too evident when she was photographed seated alone in front of the Taj Mahal.

- March: Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson announced they were separating.

- April: Princess Anne and Mark Phillips were divorced. They were already separated, and news had recently broken that he had fathered a child a few years earlier with a New Zealand woman.

- June: the ‘tell-all’ book Diana: Her True Story, written by Andrew Morton, was published. It revealed Diana’s deep unhappiness, including an attempted suicide.

- August: Photographs appeared in the press of Sarah Ferguson in an intimate relationship with her Texan financial advisor.

- November: Windsor Castle, the beloved retreat of the Queen just outside London, went up in flames. A spotlight in Queen Victoria’s chapel had ignited a curtain, and the fire then spread to the roof and other locations. It destroyed 115 rooms, including nine state rooms. (The castle was restored at a cost of £36.5 million, a cost equal to almost £90 million in 2022.)

Only the last of these was not a problem of relationships within the royal family. The year was truly an annus horribilis for the Queen, sadly not her only one. There is no family without its troubles.

If worries and woes are the norm, what are wise ways to respond and cope? There are probably many, but here I’ll suggest four.

Let’s be honest. I like the inscription on the grave stone because of its honesty. Not everyone in the family had been good, and some were bizarre to the point of being unbelievable. I’ve sat through funeral services where the deceased person is made to sound like the greatest of all saints, except everyone knew he wasn’t. Someone might well have turned to his neighbour and asked, ‘Whose funeral was that, because the preacher certainly wasn’t describing Joe?’ Our family troubles shouldn’t be turned into headline news, but neither should we pretend everything and everyone is wonderful. A reasonable honesty about life and relationships is good.

Let’s be comforted. If it’s news to you that having odd, difficult or bad people in your family is normal, it may reassure you that, after all, your family isn’t unique. Over the years Alison and I have received Christmas newsletters which mention only great achievements for someone’s children and other near relations. We have looked at each other, and smiled as we said ‘our family is not like that’ and ‘we don’t believe that’s the whole story for their family either’. Sometimes the harder truths have emerged later, perhaps that someone’s marriage has broken up, or a family member has dropped out of university without any plan for what’s next. There is no place for rejoicing over anyone else’s troubles, but there is reassurance in knowing your family is not the only one with misfits and miscreants.

Let’s be caring. I was being humorous earlier about having an uncle so embarrassingly crazy the rest of the family pretend they’re not related to him. That’s not exactly true, but it’s also not exactly untrue. Sometimes families shun relatives who are weird, or super-needy, or old, or behaved badly, or who are simply unlikeable. Can that ever be right? I don’t believe it is. Yes, family members can be difficult or demanding, but they are family members and that relationship creates an obligation to care. The New Testament is very straight about family responsibility: ‘Anyone who does not provide for their relatives, and especially for their own household, has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.’ (1 Timothy 5:8)

My Aunt Milla was a nurse, her career spent mainly in challenging places with very disadvantaged people. She was hard to shock. For the last few years of her professional life, however, she was a hospital almoner (a social-service worker in a large hospital). Her work included liaising with families whose elderly mother had completed treatment, and was now fit to be discharged except she could no longer live alone. Would the patient’s family take in their mother? Most times the answer was a very firm ‘No!’ That did shock my aunt. Their children were grown up and long gone from home, so the house had spare bedrooms, but people would not look after their mother. They enjoyed their freedom, and caring for mother would restrict that. The only thing they were willing to do was put mother into a care home.

Family members are often not easy, but please let’s care for them.

Let’s be gracious. The word gracious comes from ‘grace’ which means undeserved favour. In the Bible parable, grace is what the father showed to his prodigal son, the one who took his inheritance early, then squandered it and nearly starved before coming to his senses and returning home. His father could have shunned him, but instead flung his arms around the boy and welcomed him back into the family.[1]

Our relatives know when they’re being shunned, or judged, or looked down on, or hated. I won’t pretend it’s easy to be kind to those who have hurt us in terrible ways. But – as far as possible – our goal should be forgiveness and restoration.

Some years ago, during long car journeys, I’d listen to the songs of Chuck Girard. One stood out particularly. Here’s the chorus: Don’t shoot the wounded. They need us more than ever. They need our love no matter what it is they’ve done. Sometimes we just condemn them, and don’t take time to hear their story. Don’t shoot the wounded. Someday you might be one. At one time Chuck Girard struggled with alcoholism. His song may reflect the need he once felt to be taken back into family and fellowship. What’s more, as Girard points out at the end of the chorus, one day we might be one of the wounded, and then long desperately for restoration.

Let me finish with this. Over the years I’ve often been tempted to label a colleague or a church member as a ‘problem person’, someone with a special ability to annoy me or make my life difficult. Then, one day, I realised something obvious: that if someone was a ‘problem person’ for me, I was surely a ‘problem person’ for someone else. That person would find things I said or did annoying, or my decisions difficult to accept.

The hard truth is that none of us are perfect. All of us need forgiveness and acceptance, not just from God but probably from our families too. The writer of the gravestone inscription didn’t think all his family had been good, and some were amazingly bizarre. He was a little odd himself, with the strange summary of his family and having his own name on the gravestone while still alive. But oddness is normal, and recognising and accepting that will make for happier families.

[1] The story can be found in the New Testament, Luke chapter 15. I wrote about the prodigal a few blog posts ago – see https://occasionallywise.com/2022/11/02/change/