Experience is something young people can’t have. It’s impossible to teach, learn from a book, or borrow from another person. Experience – good or bad – is what we discover during life’s journey. And, if there’s an advantage from being older, you’ve a lot of experience.

My mind started thinking about that after I came across a photo of me when I was 13. It was a semi-official picture taken at school, probably to have a photo of me in my file. I know exactly when the photo was taken because there’s a poppy in my lapel, which was the custom around the time of Remembrance Day each November.[1]

I look young, and untroubled by issues that concern adults. However, I began to wonder what my 13-year-old self would like to have known but didn’t. Were there things it would have been good for me to understand at age 13?

I’d like to have known that one day I’d have a girlfriend

I’m starting here because girls are exactly what this 13-year-old boy was bothered about. Girls were no longer a nuisance. In fact, they had become rather interesting.

But, at 13, and with only a brother, girls were a mystery to me. How could you know if a girl liked you, and what should you say to her? If only everyone was fitted with a light and when two were attracted to each other their lights would go on. But we hadn’t been fitted with lights, and the mystery remained for a few more years.

By my later teens, though, I had a wide circle of friends, and my breakthrough realisation was that getting close to a girl was less about attraction, and more about being interested in each other, about really getting to know someone, enjoying being together, sharing ideas and plans. Then, one Sunday evening, I found myself walking up a road in Edinburgh chatting to a girl who was more interesting than anyone else. Decades later, now with children and grandchildren, Alison is still more interesting than anyone else.

The 13-year-old me would have been so much more at peace if only I’d known that would happen.

I’d like to have had a career goal

Some know the work they want to do from an early age. Perhaps their ambition is to be a ballerina, an international footballer, win a Formula One championship, do research that wins a Nobel Peace Prize, invent world-changing technology, write block-buster novels. They’re good thoughts, but most will disappear when faced with massive challenges. Some, however, will dedicate themselves to a particular career path, and get there. They’ll be great doctors, top scientists, own a profitable business, or become a member of Parliament.

But I had no idea what I would do for a career. When I was eight or nine I thought I’d like to be a bus driver, or become an Automobile Association patrolman who rode around on an old style yellow motorcycle with sidecar looking for members whose cars needed rescue.[2] But these were just a child’s idle dreams, not serious career goals.

At 13 I had no idea what work I might do. However, when I was 15, my school ran a careers evening with spokespeople describing their work. One was a police officer, and he highlighted all the different specialities that existed within policing. The wide range of options appealed to me, so later I read up about police service. Then I found a problem. In those days the minimum height for men to enter the police force was 5’8”, and in my area even higher at 5’10”. I didn’t think I’d reach either of those heights, so abandoned that plan.[3] When I was 16 I began to think about leaving school,[4] but had no idea still about a career.

I’ve mixed feelings now about that lack of a sense of direction. A career goal would have motivated me about my school work, and reassured me about where my life was headed. Yet, without a particular goal, I was open to any possibility, and that may have been helpful. In the end I began in journalism, became a church minister, then led a large international mission agency, and finished by being President of a seminary in the USA. I changed my work (not just my employer) several times, something that is now considered normal. I was ahead of my time.

So, though I wish I’d had a career goal, the lack of one did me no harm. I was flexible, and accepted change when it presented itself.

It would have helped if I’d had confidence in my own abilities

When I was 13 I was moderately good at rugby. I could tackle, catch and pass the ball, and kick it well too. I was also good at cricket, not so much as a batter but as a bowler and fielder. Somehow I could flip my wrist to make the ball break sharply left, completely confusing batters as the ball zipped past and hit their wickets. And, because I had fast reactions and virtually never dropped a catch, I relished every chance to be a slip fielder.

But sport was simply enjoyable. It was a pastime, not a passion nor a career goal. What was supposed to matter to me aged 13 was my academic work. But, in that area, I had every reason to be modest with my expectations. My teachers were equally modest in their expectations of me. When I was 13 the set curriculum I had to study covered a wide range of subjects, including physics, chemistry, biology and Latin. When I was 14 I was allowed to narrow my schedule. I dropped all the sciences and Latin with the approval and relief of my teachers. After another year I was due to take national exams. My teachers wouldn’t present me for the German exam since I was bound to fail. And fail was exactly all I achieved in three subjects, French, Maths, and Arithmetic. My only successes were in English and history, and I passed those at a higher level the following year.

But, with that track record, I had no confidence in my abilities. I never imagined I could be admitted to university, and no-one ever suggested I should try. In fact a career advisor advised me to start work in a department store sweeping the floors, and perhaps I could work my way up to being a store manager. I swept that idea aside, but he was not the only one with low expectations of me in those early to mid teen years.

For a while that was discouraging and unhelpful. Yet, looking back, it may have triggered a desire to prove them all wrong. Which was probably the best response.

I wish I’d understood that not all people are good

I grew up in a loving family unit with two parents and a brother. Nearby were aunts, uncles, and cousins we saw regularly. Our town was relatively crime free, big enough to have shops for everyday needs but small enough that traffic jams were unknown. I walked or cycled to school, came home for lunch, and, when daylight allowed, spent evenings playing football or cricket with friends. During summer holidays from school I’d play golf in the morning and cricket in the afternoon, and when I wanted a change I’d play cricket in the morning and golf in the afternoon. I had a very privileged early life.

The only downside is that it was also a very protected life. When I was 13 almost all I knew of the ills of the world was that I should never go off with a stranger, that a girl in my class had died from a serious illness, and a boy had fallen from his bike in front of a lorry and been killed. But I didn’t know of anyone dying of cancer, anyone getting divorced, anyone without food, anyone committing a major crime. My parents would watch the news on TV, but, as far as I was concerned, bad things happened far away. I had a sheltered existence.

That resulted in an unhelpful innocence, a naivety that everyone is kind and good and no harm can befall you. Of course we must not make children fearful or untrusting. But – as with many things – I wish there had been an age-appropriate way of making me aware that bad things happen in this world.

From my later teens and into my twenties I was a journalist with a national newspaper. That gave me a rude awakening to tragedies and evils. I attended car, rail and plane disasters where mangled bodies were pulled from wreckage. I sat through murder trials, such as the killing of a 15-year-old girl by beating and strangling.[5] It shocked me that one person should so violently and deliberately end another person’s life. There were cases of gang warfare, often drug related. Some politicians were considered corrupt, others attention-seeking. I attended court sessions and local government meetings which were supremely tedious. Some of my colleagues were deep in debt, unfaithful in their marriages, addicted to alcohol, or dying of lung cancer. Of course there were also ‘good news’ stories, but I was used to them from my upbringing. It was the ‘bad news’ that jolted me into a broader understanding of the world.

It would have helped me, certainly by the time I was 13, to have learned something about the harsher sides of life.

I could have known more of how poor most of the world is

My Aunt Milla – whose working life was mostly as a community nurse – rarely spent much on her housing. During two periods she lived in run-down tenements. The first had no toilet facilities inside the building. None at all. Instead there was a small hut out the back which contained a simple toilet. No wash-hand basin, and sometimes no toilet roll, only torn sheets of newspaper which were guaranteed to leave their mark. Day or night, perhaps in pouring rain, the ‘need to go’ was an unpleasant adventure into the outdoors to use the ‘privy’. Milla moved upmarket with her later tenement living. There still was no toilet in the flat, but there was one on the ‘half-landing’ (so named because it was up some steps from the level of flats just below and down some steps from the level of flats above). Since there were two flats on each level, the toilet might be shared by four households. Perhaps queues were avoided only by exploring for ‘vacancies’ at toilets on other half-landings.

These were poor facilities – unhygienic and inconvenient – but were common in many towns and cities, and not just in the UK. We often stayed with my aunt, and therefore used the outhouse or half-landing toilets many times. At home we had indoor plumbing, but I knew many lived with facilities like my aunt, so never thought of her situation as poor or bad. When I was 13, I had no idea at all that most of the world lived in very much worse circumstances.

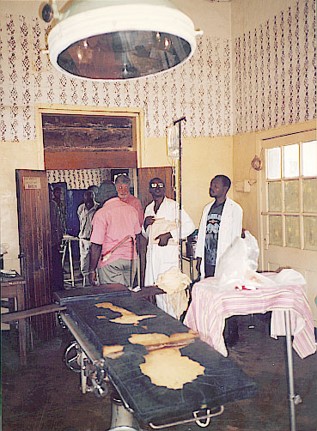

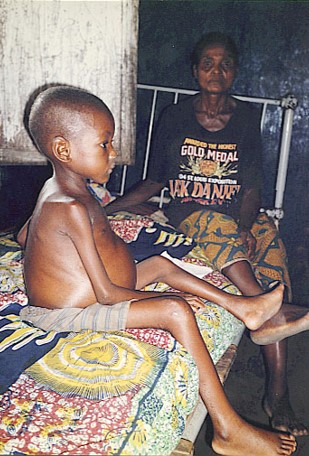

Almost 30 years later I visited remote desert areas of Pakistan, sleeping overnight in tribal villages. Toilet facilities? The far side of the sand dunes. In a mountainside village in Nepal, there was an outhouse for toilet use, but it was no more than a small enclosure around an open hole with charcoal six feet below to (unsuccessfully) deaden the stench. In a remote Congo village I thought that children were wearing dirty and torn t-shirts as play clothes, then realised those t-shirts were their only clothes. There I also met a mother with seriously malnourished children, hoping for help from medical missionaries. I saw many small houses with damaged roofs. I was told: “There’s no longer anyone skilled in repairing roofs. When people don’t have money to buy food, no-one pays to have their roof repaired.”

I could multiply these stories, but won’t. The hard truth is that a large part of the world’s population live in poverty. I never knew that when I was 13. As children grow up, and gradually decide on lifestyle and career priorities, shouldn’t those priorities take account of world need? In affluent countries, we shelter children from harsh realities. That’s understandable, but should they not know billions are less well off, and their needs may matter more than our comfort?

I wish I’d known what I needed to do for God to become real in my life

God was never absent from my life (nor is he from anyone’s), but when I was 13 I didn’t relate much to God other than with some prayers. My mother told me several times that she made a special commitment to God when she was 13. That commitment coloured everything she did, and a lot of her time went on supporting church activities and helping neighbours. So, when I became 13, I imagined something might happen in my life to make me a Christian like her. Nothing did, and as the next few years passed I wondered if it ever would.

What I’d failed to realise is that I had a responsibility to reach out to God. I was waiting for God to invade me while, in a sense, he was waiting to be invited. That did all change when I was 18, and I’ve written about that before (https://occasionallywise.com/2021/02/20/serious-business/).

It wasn’t that I was ignorant about the Christian message. I just needed to respond to it. Thankfully I was only five years beyond 13 in doing so. But, if I’d known sooner, my life would have changed much earlier.

–

Writing this blog post about what I wished I’d known when I was 13 has kept generating more thoughts than I’ve recorded here. Perhaps I’ll set them down another time. And one day I may also write things I’m glad I did know when I was 13. That seems just as important a subject.

I’d encourage you to think what you wish you’d known when you were younger, and what you’re glad you did know. You might be surprised about your conclusions.

[1] Fighting in World War I ceased at the 11th hour of the 11th month in 1918, commemorated annually throughout Commonwealth countries ever since. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remembrance_Day

[2] There’s a good photo of an AA motorcycle and sidecar here: https://www.theaa.com/breakdown-cover/our-heritage-vehicles

[3] Actually I did reach 5’8” but my interests by then lay elsewhere.

[4] In Scotland, the school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and though from the 1940s there were plans to make the minimum age 15 that was never made law. The minimum age was set at 16 in 1973.

[5] The case set a new legal precedent because the accused was identified by having left unique bite marks on his victim’s body. See https://www.dentaltown.com/magazine/article/7528/the-biggar-murder-some-personal-recollections