Was the death toll from the Great Fire four or four thousand? Did the blaze end the Great Plague? Who or what emerged hairless but alive from the heart of the inferno? How long was it before the bakers of London apologised that one of their own had started the fire? Did someone commit suicide by falsely confessing he set London alight?

Answers to these questions and much more will follow.

There were both serious and less serious consequences from the Great Fire of London. This is the fourth and final part of the story of the 1666 Great Fire, and I’ll explore a variety of outcomes here. Episode 1 of this series describes the beginnings of the Great Fire in a bakehouse in Pudding Lane, and explains why it spread quickly.[1] Episode 2 shows how the fire intensified, with residents fleeing the city and leadership failing.[2] Episode 3 records the fire’s relentless spread; St Paul’s Cathedral is lost but the Tower of London is saved.[3] The footnote links in this paragraph will take you quickly to those earlier episodes.

The Great Fire began in the early hours of Sunday, September 2nd, 1666. Most consider that the destruction was over by the end of Wednesday 5th, four full days later.[4] But, of course, the consequences of the fire lasted far longer than the blaze.

In this final episode, I’ve summarised some of the major effects of the Great Fire under several headings. A few oddities I’ve uncovered along the way are mentioned under ‘Eleven curious details’ near the end.

I’m aware this section is lengthy. I hope you’re willing to read it all, but if time or energy fails you, I’ll admit the parts that most interested me have the headings: ‘Death toll’, ‘The plague’, ‘The lust for vengeance’ and ‘Eleven curious details’. You may especially appreciate those sections too. I’d like to believe you would also find my final summing up under ‘Lessons from the Great Fire’ important.

Extent of damage

All reports of the physical damage done by the Great Fire are not identical. However, the figures below are commonly cited.

Property and land destroyed:

- Houses: 13,200-13,500, leaving 130,000 people homeless

- Churches: 87

- Significant buildings: St Paul’s Cathedral, Baynard’s Castle, The Royal Exchange, the Custom House, Bridewell Palace, The Guildhall, 52 livery company halls and three city gates.

- Acreage: approximately 436 acres, equal to more than four fifths of London. Some quote the figure as 86% of the city.

- Total financial loss of the damage was approximately £10 million (equivalent to £1.79 billion in 2021). To put the £10 million in perspective, the annual income of the city was only £12,000.

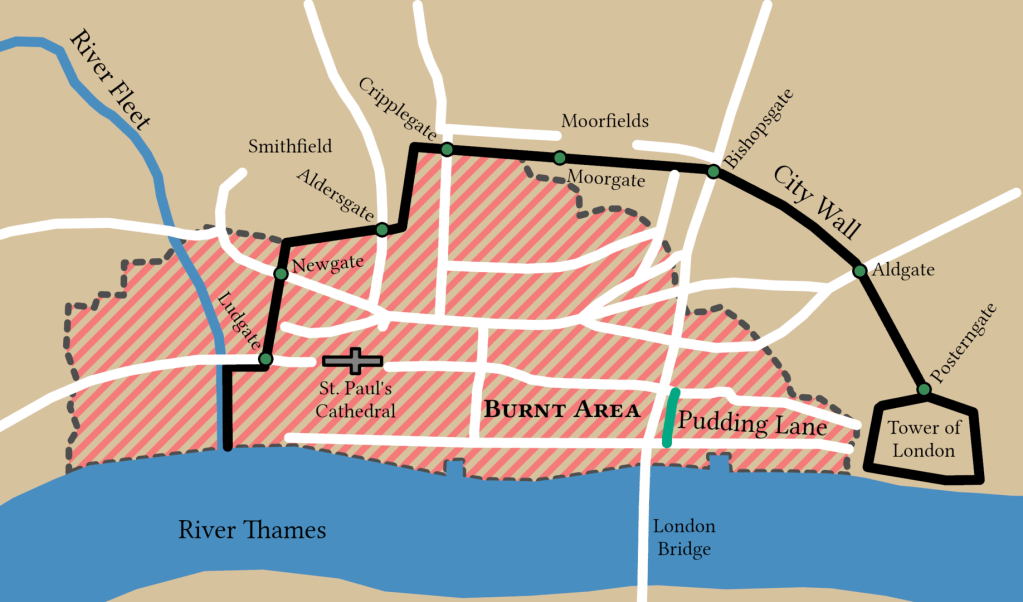

The map shows the final spread of the Great Fire across London. The area surrounded by a bold black line is the city surrounded by the ancient Roman-built walls. The locations of the various gates are marked. The fire originated in Pudding Lane indicated by a green line. The fire mostly drifted westward, driven by the wind, and spread to areas outside the walls. But – inside those walls – the greatest part of London was destroyed.

People:

Bald statistics do not, of course, tell the human story. In addition to loss of life (to which we’ll come next), the loss of homes was devastating. The majority of those forced to camp outside the city walls in fields, or living in primitive shelters among the ruins inside the city, really were homeless. They had no immediate means of rescuing their situation. There was virtually no such thing as house insurance. Besides, the large majority were renters. They didn’t know if their landlords had the finances to rebuild homes, if they’d wish to rebuild homes, and, even if they did, whether those homes would be leased to them. Meanwhile the refugees’ employment was largely gone. Some would be engaged in rebuilding projects, but for the foreseeable future the ordinary factory worker or tradesperson had lost their livelihood. Tens of thousands, then, were now utterly insecure with no idea how they’d survive.

Death toll

There are very varying ideas of how many died in the Great Fire. Numbers extend from a handful to a large multitude.

Official accounts written soon after the fire put the death toll in single figures. Some say four, others six or perhaps eight. And there are modern writers who would argue that people had time to escape so these numbers may well be accurate.

However, there are several reasons to be cautious about a very modest death toll:

- We should ask, ‘Were there reasons to understate the death toll?’ For example, perhaps the largely absent Lord Mayor Bloodworth[5] wished to play down the consequences of his failure of leadership. Other civic leaders – thinking of future investment in England’s foremost city – may have wanted to minimise the devastating consequences of the fire.

- The late 1660s was an age without anything like modern forensic science. No-one picked their way carefully through the ruins of thousands of fire-ravaged homes for skeletal remains. Perhaps, in any case, there would be virtually no remains. Those who choked and collapsed because of smoke or intense heat may well have been cremated by the intensity of the flames which swept through their property.

- Attributing deaths to any disaster is not simple. Issues of how, where and when someone died arise. To illustrate, think about a large battle during a war. When a death toll is stated, are we being told the number who died during the battle? Or does the death toll include those who were wounded, lived for several days or even a few months and then died of wounds sustained during the battle? Then what about those so severely scarred mentally by what they went through they later took their own lives? Defining one number for casualties is complicated. So it is with the death toll of the Great Fire. Are very low numbers of deaths referring only to those who died in the flames? If so, is it not better, for example, to include the large number who perished later because they were still camped outside the city walls when winter fell? Those poor people didn’t die in the fire, but they did die because of the fire.

So, how many deaths can really be attributed to the Great Fire?

Some modern historians still support a death toll in single figures, albeit accepting that some deaths would have been unrecorded, and that refugees also died later camped in fields. Another historian supports a number greater than the lowest figures but thinks it likely the total would not run into the hundreds. Neil Hanson draws attention to known deaths because of hunger and exposure during the cold winter after the fire. He also believes that while some foreigners and Catholics were rescued from mob-lynching, many violent deaths went unrecorded. Hanson also supports the theory that the heat at the heart of the firestorms was much more intense than an ordinary house fire, and thus able to near fully consume bodies. He believes that instead of four, six or eight the death toll was “several hundred and quite possibly several thousand times that number”.[6]

The writers of the Short History of the Great Fire of London podcast researched parish records for deaths before the fire, for the year of the fire, and then for a short time after the fire. They find anomalies in those figures, perhaps suggesting that the recording of deaths was unreliable. What I find even more enlightening is a comparison they make with deaths linked to the Great Fire of Chicago. The Chicago fire was not until 1871, but there are similarities with London’s 1666 fire – population size, density of wooden buildings, time of year, and presence of a strong wind. Deaths were more properly recorded in the late 1800s, and between 200 and 300 are attributed to the Chicago fire. Thus, the writers conclude, the London fire likely also resulted in several hundred deaths but probably not thousands.[7]

Given all the limitations of a major disaster in the 17th century, we will never know an exact number of deaths because of the Great Fire of London. My own view is that the low numbers are unlikely, but so are the extremely high guesses.

Planning a new London

Before the fire, the writer John Evelyn compared London to the grandeur of Paris and described Britain’s largest city as a “wooden, northern, and inartificial congestion of houses”. That’s a confusing mix of words, but he’s trying to describe how poorly designed and built London was. For Evelyn, the city was an unorganised sprawl of unattractive streets and homes.

Within days of the Great Fire ending, many – including King Charles II – determined the rebuilt London would be much better. The city would be redesigned, and homes built to a much higher standard.

Work began almost immediately to clear massive heaps of debris, almost all of it unusable. A special Fire Court[8] was set up to decide property disputes. Many of those were arguments between tenants and landlords about who should pay for rebuilding. Cases were decided quickly with verdicts based on ability to pay. Without the Fire Court legal issues could have lasted years and seriously delayed rebuilding.

Right from the start drawings of a new London flooded in. Many of the submissions were sent direct to the King. Some came from ordinary citizens with radical ideas, and some came from people with planning experience, including Christopher Wren. Most proposals involved a grid system of streets, a significantly different pattern to how London had evolved. There were also plans for boulevards and piazzas similar to those in French and Italian cities. Along with the drawings came bold and romantic statements of rebirth, that a marvellous new London would emerge from the ashes.

But almost none of that ever happened.

Wren’s plan, for example, failed because a very large number of property titles would have had to be redefined, an almost impossible task because land in London was owned by many people. Besides, no-one was willing to wait for complex plans to be assessed. With little building control, work had already started on building new homes on the scorched earth. People needed houses simply to survive. So London was rebuilt much as before.

However, some new regulations were imposed.

One of the reasons the fire had spread so easily and quickly was the density of the housing. There were almost no gaps between houses. Streets were very narrow, and roofs overhung so far they virtually joined with adjoining homes, even those on the opposite side of the road. Another reason the fire took such a strong hold was that most houses were made of wood which, when dry, was perfect fuel for the fire. So, the new construction regulations required all buildings to have at least a stone or brick facing. Streets must be widened and new pavements[9] built. Two new streets were created. No houses must obstruct access to the River Thames, and better wharves must be built there. The cost of building materials was regulated, as were the wages of workers. A deadline of three years for rebuilding was set; if not met, land could be sold. In the end most private rebuilding was done by 1671.

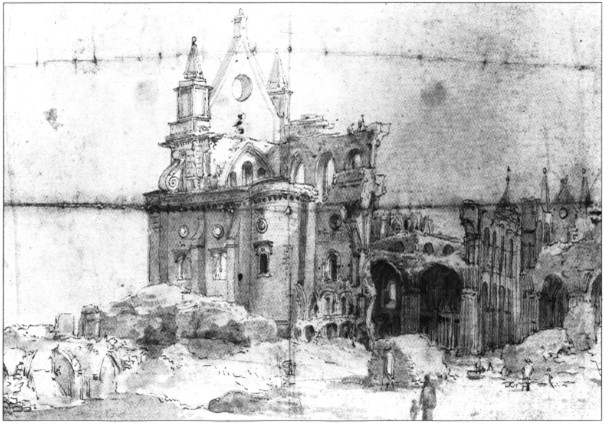

Supervision of much of the reconstruction was entrusted to a six-person committee, with Christopher Wren as the ‘Commissioner for Rebuilding’. Wren was born in October 1632, therefore still just 33 at the time of the Great Fire. Though his general plans for a new London were mostly rejected, he did design 51 new city churches and The Monument (more on which shortly). His most famous achievement was designing and overseeing the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral. The excellence of Wren’s work was recognised with a knighthood on 14th November, 1673 (hence he had the title ‘Sir’ after that date).

Overall it took almost 50 years before the fire-ravaged area of London was rebuilt. It was 1711 until the reconstruction of St Paul’s was complete.

The Monument

Because the Great Fire of London was so momentous, a decision was made by the King to build a commemorative monument close to where the fire started. Some attribute the design work of a monument to Christopher Wren, others to surveyor Robert Hooke – very likely they combined their skills. Work began on a Doric column in 1671 and it was completed in 1677. Known simply as The Monument, it stands 202 feet tall (61.5 metres) and is located exactly 202 feet from where the fire began in the Pudding Lane bakery. At the very top is a drum and copper urn from which flames emerged, symbolizing the Great Fire.[10]

On the column were sculptures and engravings telling the story of the fire. In 1681 a plaque was added attributing blame for the fire. An official enquiry determined the Great Fire was due to “the hand of God, a great wind, and a very dry season”, but, with anti-Catholic feeling running high, the inscription on The Monument put the blame on the ”treachery and malice of the Popish faction”. The inscription was removed in 1830.

Fire Insurance and Fire Brigade

The Great Fire made people think more seriously about better fire safety and the cost of repairs. In 1680 Nicholas Barbon set up the ‘Fire Office’, an insurance company.[11] Other similar companies were soon established.

By 1700, those fledgling companies had the common sense to realise it was probably cheaper to extinguish fires than pay for repairs. They set up their own fire brigades, and had plates fastened to houses naming which company insured that property. If a fire brigade of another company put out the fire, the insurers had reciprocal arrangements so the correct insurer would cover the cost.

Eventually even more common sense prevailed. The most efficient fire-fighting system would be one unified force covering the whole of London. So, in 1833 the London Fire Engine Establishment was founded. There were numerous fire stations across the city, each providing 24/7 coverage. Floating engines were built for The Thames to tackle fires in the docks.

Now known as The London Fire Brigade, it has become one of the largest firefighting and rescue organisations in the world. It employs more than 5000 people, and in 2022 dealt with 125,390 incidents, of which 19,297 were fires.

The plague

The Great Plague (or Black Plague) began to spread in early 1665. It was deadly, and the number of victims rose quickly. In London about 15 per cent of the population died in the plague’s first year. That could be as many as 75,000 deaths, a huge number.

There were plague victims also in 1666, then in September the city was consumed by the Great Fire. And afterwards the Great Plague faded away. Why? The obvious conclusion is that the insanitary houses – overrun with rats and fleas which spread the plague – were gone, so the epidemic was halted. The tragedy of the Great Fire eradicated the tragedy of the Great Plague.

Except it didn’t. Sometimes an obvious conclusion is a wrong conclusion.

The Museum of London says that the idea that the Great Fire stopped the Great Plague is the most talked about myth they hear.[12] It’s nice to think there was a silver lining to the Great Fire. But the idea isn’t true. The Museum lists five reasons:

- The Great Fire burned only about a quarter of the overall London metropolis. It could not have killed off the plague for the whole ‘Greater London’ area.

- Houses built after the fire had stone or brick-faced walls, but hygiene and sanitation did not significantly improve.

- Areas where the plague was worst – Whitechapel, Clerkenwell, Southwark – were not affected by the fire.

- The number of plague-related deaths was already declining long before the fire.

- People in London still died from the plague after the Great Fire was over.

The Great Plague’s major death toll occurred during 1665-66, and the Great Fire broke out in September 1666. So it’s not surprising that the second is assumed to have eradicated the first. But that is a wrong assumption. The Museum says: “We are still not sure why the plague did not return to our shores after it faded out in the 1670s but it wasn’t due to London’s 1666 fire”.

The lust for vengeance

During the Great Fire, anger became rage and rage became a lust for vengeance. In the minds of many, the destruction of London could not be an accident. Farriner protested long and hard that the fire did not start in his bakery. He had double checked his ovens before he went to bed. Many were willing to believe him. A fire like this had to be a deliberate attack. A Parliamentary investigation blamed the fire on the hand of God, the strong wind, and the dry season, but those reasons were not enough. Enemies of London and of England were surely responsible. Blame was directed at Catholics and foreigners.

The anger was fed by homelessness and near starvation. Camped outside London while autumn temperatures dropped, people were dying. Evelyn wrote: “Many (were) without a rag or any necessary utensils, bed or board… reduced to extremest misery and poverty”. The King, Charles II, was so afraid these refugees would rise against the monarchy, he ordered daily supplies of bread to be brought to the city and new markets created.

Charles went even further, encouraging people to move away from London and ordering neighbouring towns and cities to permit incomers to engage in their trades in these new locations.

These were good measures, but still thousands suffered. The mood was volatile. For those living in and around London there was an overwhelming longing to hit back at those responsible for their misery. Before the fire had even been fully extinguished, a rumour spread that French and Dutch troops were approaching. Londoners would not wait to be slaughtered, so mobs rushed through the streets attacking foreigners. Soldiers had to intervene to stop the violence.

In the months following, the lust for vengeance was undiminished. It was inexcusable to attack people simply because they were foreigners, but Londoners were traumatised and panicked. As still happens today, the general population didn’t entirely trust official statements from central authority, in their case from the King. And – with no press or TV or internet – they were fed a strong diet of rumours. And since the only rumours worth spreading are those which are frightening or threatening, people became terrified and angry.

As well as rumours there was (what we now call) ‘fake news’. The official parliamentary enquiry into the fire[13] heard evidence from many people, including those who suspected the Dutch or French or Catholics. The committee recorded everything that was said, but rejected the suspicions of arson and ruled that the fire was an accident made worse by the strong wind and dry season. But someone collated the testimonies of those who blamed foreigners, made those statements into a pamphlet, and leaked it to the public. By now it was obvious there was no Dutch or French invasion, so the story spread that shadowy Catholic agents had started the fire.[14]

In fact, a man who swore he was Catholic had already been arrested, tried and executed. His name was Robert Hubert.

Hubert was a watchmaker who originated from Rouen in France. He had come to London, but, as he headed later for east coast ports, he was stopped just outside the city. Authorities questioned him. Hubert admitted he was a member of a gang, that the fire was a French plot, and he had started the fire. He was charged, and imprisoned in one of the unburned jails.

There are several reports that Hubert was not fully able to explain himself. Some have said he was simple-minded, and may not have realised the implications of his confession, or had imagined the story he told. It’s also possible he was tortured.

Hubert’s story was inconsistent. Originally he said the French gang was 24, but then he dropped the number to just four. He stated that he started the fire in Westminster, but then learned no fire had ever reached there. Where the fire actually began was mentioned to him, so his story changed to how he had thrown a fire grenade through an open window of the Pudding Lane bakery.

He was brought to trial in October 1666 at the Old Bailey courts. There were doubts about his evidence. Some said he had not even been in London when the fire started. He insisted he was a Catholic, but those who knew him said he was Protestant and a Hugeunot.[15] His story of throwing a grenade through a window was nonsense, because the bakery in Pudding Lane had no windows. Besides, Hubert was crippled and incapable of throwing a grenade. The Lord Chief Justice, who presided over the trial, said Hubert’s confession was so disjointed he couldn’t possibly believe him guilty. But Hubert insisted he was guilty. McRobbie says that put officials in the strange position of trying to prove he hadn’t done what he said he did. But Hubert was adamant that he had started the fire, so was found guilty and hanged at Tyburn on 29th October, 1666.

Hubert was innocent. Evidence soon emerged from the captain of a Swedish ship that he had been on that ship in the North Sea when the Great Fire started. He did not arrive in London until two days after that. He was not a Catholic, not a member of a French gang, and certainly had not started the fire.

Perhaps the strength of his confession meant a guilty verdict had to be given. Perhaps people thought that convicting Hubert would end the rage of the crowds. Perhaps Hubert wanted to die. Apparently his life had been miserable, and he wanted to end it. In that case, to use a phrase of McRobbie’s, Hubert committed ‘suicide by confession’.

Anti-Catholic sentiment and suspicion of foreigners continued for many years. Negative feelings do not change quickly, as many today would still testify.

Eleven curious details

One In 1681 a plaque was placed in Pudding Lane blaming ‘Papists’ for the Great Fire. In the mid-1700s it was removed. Why? Had people realised Catholics were not to blame? No. It was taken down because people stopped to read the wording and that caused a traffic hazard.

Two The Monument was designed with a 311 step internal staircase leading to a viewing platform, so Londoners could see their city being rebuilt. A mesh cage was added to the viewing platform in the mid-19th century because people had committed suicide by jumping. Some 100,000 people each year continue to climb to the viewing platform.

Three In 1986 – 320 years after the Great Fire – the London members of the Worshipful Company of Bakers apologised to the Lord Mayor for the fire. They placed a plaque in Pudding Lane acknowledging that one of their own, Thomas Farriner, was in fact guilty for causing the Great Fire.

Four Sir Christopher Wren’s range of professional interests included astronomy, optics, cosmology, mechanics, microscopy, surveying, medicine, meteorology. He was also an inventor of scientific instruments.

Five Wren began studying architecture in Paris in 1665. By the next year he was back in London, where he drew his first design to improve the rapidly decaying (Old) St Paul’s Cathedral. One week later the Great Fire began in Pudding Lane on Sunday 2nd September. On the evening of Tuesday 4th September embers landed on St Paul’s and before morning the building was gone. Wren’s masterpiece, the new St Paul’s Cathedral, was completed in 1710.

Six Sir Christopher married twice. Though neither wife lived long there were two children from each marriage. Wren died aged 90 years, and of these years was married for only nine.[16]

Seven Though Wren’s designs for a new-look London were never implemented, he was honoured in 2016 (the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire) with a Royal Mail stamp illustrating him presenting his plan.

Eight A central shaft in The Monument was created as a scientific instrument for the Royal Society. It included a telescope and a space to enable experiments on gravity. However, the vibrations of nearby heavy traffic spoiled those experiments which were soon discontinued.

Nine On Wednesday 5th September, 1666 – the fourth day of the Great Fire – the diarist Samuel Pepys witnessed a cat being rescued from the ruins of the fire ravaged Royal Exchange. He wrote: ‘I also did see a poor cat taken out of a hole in the chimney… with the hair all burned off the body, and yet alive’.[17]

Ten St Paul’s Cathedral famously survived the ‘Second Great Fire of London’, the World War II London blitz with incendiary bombs.

Eleven John Evelyn summed up what the Great Fire had done to his city in six words: ‘London was, but is no more’.

Lessons from the Great Fire

There have been many lessons as the story has unfolded:

- Something small, such as one spark, can have massive consequences

- The unimaginable should have been imagined, and preparations made

- Clear and decisive leadership is vital to deal with a catastrophe

- How ready people are to find someone to blame, and take the law into their own hands. The sad truth is that people want villains and want vengeance.

- Sometimes you can’t wait for permission; you must act now. That’s what happened when the garrison at the Tower of London used gunpowder to demolish houses between the fire and the Tower. They’d waited for help which never came. So, before it was too late they took responsibility for halting the flames, and thus saved the Tower.

- Nowhere is immune from harm. Many thought the stone-built St Paul’s Cathedral was safe so they put all their possessions inside. That was a bad decision. The Great Fire was greater than the resistance of the cathedral, and the building and everything inside was lost.

- Often you can’t control an outcome. The best firefighting efforts did not stop the Great Fire. What halted its spread was that the easterly wind subsided. The flames were no longer driven westward, thus providing an opportunity to extinguish fires.

Here’s my final lesson. I began this series by saying one spark from a fire left smouldering under an oven caused the Great Fire. Just one spark cost vast amounts of property to be destroyed, many lives lost, and a huge financial cost to rebuilt London.

We neglect the small or ordinary things of life at great peril. Those seemingly small things can be personal, like time with family or looking after our health. They can be the background factors when running a business, like getting to know colleagues or being careful about contracts. They can be the affairs of state or global relationships, such as misunderstanding or neglecting an issue, or threat, or contrary voice.

There’s a saying that large doors swing on small hinges. Extremely large consequences flow from small, seemingly unimportant matters.

Bad things will always happen. But some can be avoided by careful attention to details, by preparation for worst case scenarios, by wise and decisive leadership, and the other lessons taught to us by the Great Fire.

My major online resources for this series on the Great Fire are listed at the foot of the first episode. See https://occasionallywise.com/2023/01/28/great-fire-of-london-1/

[1] https://occasionallywise.com/2023/01/28/great-fire-of-london-1/

[2] https://occasionallywise.com/2023/02/10/the-fire-that-changed-the-weather/

[3] https://occasionallywise.com/2023/03/18/the-great-fire-defence-and-disaster-but-the-end-is-nigh/

[4] Some record that the remains of some buildings continued to smoulder for several months.

[5] Bloodworth’s failings are detailed in the first episode of this series, https://occasionallywise.com/2023/01/28/great-fire-of-london-1/

[6] Hanson, Neil (2001), The Dreadful Judgement: The True Story of the Great Fire of London. Doubleday.

[7] Details of the Short History of… podcast are given at the end of part 1 of this series.

[8] The Fire Court operated through most of 1667 and 1668, and again between 1670 and 1676.

[9] Pavements = sidewalks in America.

[10] Details from the website of The Monument – https://www.themonument.info/history/introduction.html

[11] These details and others to follow from the Museum of London: https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/great-fire-london-1666

[12] Details here and following from https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/three-myths-you-believe-about-great-fire-london

[13] The official investigation began just over three weeks after the Great Fire started.

[14] Information here and following predominantly from Linda McRobbie’s excellent article: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/great-fire-london-was-blamed-religious-terrorism-180960332/

[15] Hugeunots were certainly Protestant, and many fled France to avoid Catholic persecution.

[16] From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Wren

[17] Museum of London: https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/cats-in-museums-feline-history-london