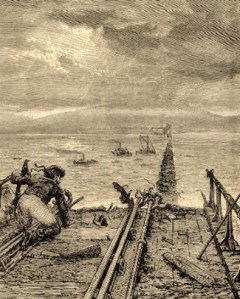

It’s 1853, three years after Thomas Bouch launched his ‘floating railway’ over the Firth of Forth. But – though trains are now being ferried over the river – Bouch is disappointed and frustrated.

Why is he dissatisfied? There are fundamentally two reasons.

First, ferrying trains is not a great solution. Certainly Bouch’s employers in the Edinburgh and Northern Railway are happy – they’ve launched a similar ferry to cross the other east coast estuary of the River Tay. But the ferries carry only a train, not its carriages. That makes everything awkward. Here’s what happens for a train leaving Edinburgh and going north:

– leaves its first carriages on the south shore of the Forth

– gains its second carriages on the north shore of the Forth

– leaves its second carriages on the south shore of the Tay

– gains its third carriages on the north shore of the Tay.

Only after all that does the train have an uninterrupted journey north to Aberdeen. All the transitions before that are time-consuming and logistically complicated.

Second, ferrying is also a horrible experience for passengers. Think how the journey just described is for them. Trains are unheated so they arrive at the Forth already chilled, stand on a pier as the wind whips off the water, clamber on board a ferry which has no shelter for passengers, so they huddle beside the train or boxes or carts while the ferry sails through rough seas. Then they do it all again when they get to the Tay. They’re frozen, miserable and frightened. They’ve occupied three different sets of carriages, walked down or up four piers, and stood on open decks across two wide estuaries. No-one thinks this is a good experience.

Bouch agrees. There’s a centuries-old saying that you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear – if something is fundamentally bad you’ll never make it wonderful, no matter what you do. His ferries are better than nothing, but they’ll never be a good solution to crossing the east coast of Scotland estuaries.

Bouch is also frustrated. His goal and his passion is to build bridges over the rivers Forth and Tay, not organise a ferry service. Bouch had a self-confidence which some would consider arrogance. And a boldness many would think reckless. That’s before mentioning his super-abundance of ambition and determination.

Rather than sticking to a diet of dissatisfaction, in 1853 he informs his employers, now called the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railways Company, that he wants to build a bridge over the Tay. They don’t take long to answer him. Bouch gets a near-instantaneous ‘no’, and he’s told his idea is insane. Bouch is not in the least happy with that response. Soon after he resigns and establishes his own consultancy firm.

The next few years saw two trends among rail companies: the amalgamation of firms and fierce competitiveness between them to establish the best route north. Then Bouch’s old company was consumed by the North British Railways Company, and Bouch believed new leadership meant new opportunity. He knew the company was desperate to improve the northern route, so in 1860 he approached the North British directors promising he could build bridges over both the Forth and the Tay.

This time Bouch is not rebuffed. It’s a new and more optimistic age, and Bouch leaves with a commission to put his plans on paper.

For the Firth of Forth Bouch planned a lattice-girder bridge. Gardeners know about training plants up a wooden or plastic lattice structure. A lattice bridge is fundamentally the same, a criss-crossed web design, strong and resistant to bending. Perhaps the most famous lattice structure is the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Bouch’s design was not a problem, but his proposed location was. The river between North and South Queensferry was too deep, so Bouch planned to build his bridge five miles upstream where it was shallower. However, there was a problem. Yes, the depth from surface to river bed was shallower, but below that river bed was more than 200 feet (61 metres) of mud. Mud could not support the piers of a bridge.

Or could it?

At the end of the last blog, I asked if there was ever a serious proposal for bridge supports simply to float in the river. Bouch’s proposal was almost that.

Bouch wouldn’t be stopped by 200 feet of mud on the river bed. He pressed forward with a plan for a two-mile bridge held up by 61 stone piers. Those piers would not sit on rock but on mud. His logic was like this: think of walking on wet sand – your footprints press down but they don’t keep sinking because the sand compresses and holds you up. Bouch’s piers would so compress the mud that the piers would sit – or float – firmly in place.

Convinced? Bouch was, but many were not. Not for a bridge set in a tidal estuary where the water was never still, and, on stormy days, would experience turbulence above and below the surface. An official enquiry studied his plans, and asked hard questions. But Bouch stood firm, showed great confidence, and argued his bridge would stand strong. Remarkably Bouch was given a ‘green light’ and in 1866 a beginning was made.

Work started in June and in August it was stopped. Because of new concern about the design? No – it stopped because of financial deceit. For some time the accounts of the North British Railway Company had been falsified to show profits which never existed. The books had been misrepresented, well and truly cooked, and the company was actually in serious financial trouble. Shareholders were up in arms. One day company directors turned up at the Forth, ordered that work stop immediately, and the builders’ employment was terminated with immediate effect.

Once more Bouch was thwarted. He was about to bridge the Forth, and suddenly he wasn’t. The disappointment was enormous.

However, Bouch was Bouch. Though he was down, he was certainly not out.

In the last blog, I also said we’d find out why Thomas Bouch was hired and then fired. That story comes next.

The action now moves 40 miles north, to the River Tay.

The North British Railway Company is being revived under a new chairman, John Stirling. In 1864, with Bouch at his side, Stirling asks officials in Dundee to provide financial support for a bridge over the Firth of Tay. They agree, and work begins in 1871. (I told the story of the Tay Bridge in an earlier blog. You can find it among those posted here: https://occasionallywise.com/2021/10/).

Bouch was not only responsible for the design of the Tay Bridge, but for its manufacture, construction, and maintenance. Everything was under his control.

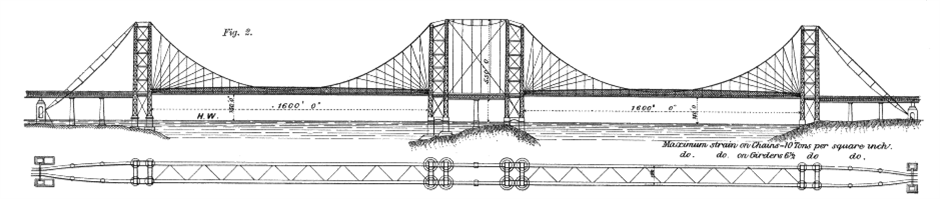

But the work at the Tay did not get Bouch’s sole attention. By 1873 he had a new design for a bridge over the Forth. This bridge could be built over the deep water between North and South Queensferry because it would be a suspension bridge, with one of its towers securely anchored on Inchgarvie island, approximately half way across the river. (There is a map showing Inchgarvie island in my last blog.) The towers of the bridge would be 600 feet (183 metres) high, with 1600 foot (488 metre) spans in either direction from the centre tower. Steel chains would hold two railway tracks.

Attrib: Wilhelm Westhofen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

But there was new concern about this design, this time not about the foundations but the ability of the bridge to withstand wind pressure. Experts gave cautious support, but they would not say this was the best possible design. Despite the concerns, the official Act permitting construction was passed in 1873, and a consortium of railway companies formed The Forth Bridge Railway Company to build the bridge.

At first nothing happened. For one thing there was insufficient money to build. For another, the attention of the North British company was on the Tay Bridge’s construction. No work took place at the Forth until September 1878 (four months after the official opening of the Tay Bridge). Mrs Bouch laid a foundation stone, and by the next spring brickwork appeared on the western edge of Inchgarvie (and can still be seen today).

And not much more was ever done. On a late December evening in 1879 an immense gale blew through the Tay estuary. The northern-bound evening train made its way on to the Tay Bridge. As it passed through the central high girders the pressure against the bridge and the train collapsed that whole section, and every person on the train, some 75 people, perished in the waters of the Tay. What happened that night has been known around the world as the Tay Bridge disaster.

An official Court of Enquiry into the disaster began work just six days later, and took only a few months to present its report. The cause, they wrote, ‘was the pressure of the wind, acting upon a structure badly built, and badly maintained.’ Later they concluded, ‘For these defects both in the design, the construction, and the maintenance, Sir Thomas Bouch is, in our opinion, mainly to blame. For the faults of design he is entirely responsible.’[1]

Bouch disagreed with the Enquiry’s findings but, fairly or unfairly, his opinion didn’t matter. He was disgraced as a bridge designer and builder. A broken man, Bouch became a recluse, and died of ‘stress’ in October 1880. He was just 58.

Some work had continued at the Forth before the Tay Bridge Court of Enquiry report was issued. But now public opinion turned against Bouch, and pressurised The Forth Bridge Railway Company to abandon Bouch’s suspension bridge design. The majority view of public and press became one of doubt that any bridge over either estuary could be safe. All work at the Forth stopped in January 1881, and an Act of Abandonment began its passage through Parliament.

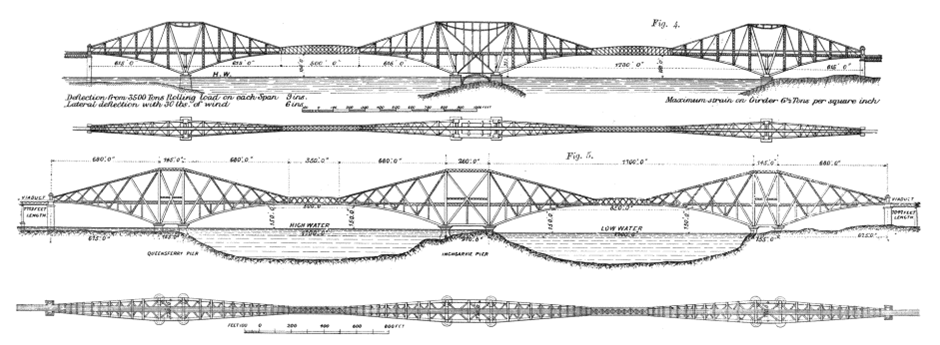

But the case for a bridge was still compelling – not least because rail companies stood to make great profits. If Bouch’s bridge could never be built, then a different design from a respected engineer might succeed. The railway companies asked engineers who knew Bouch’s plans, and knew the challenges of bridging the Forth, to consider options. One of these experts was John Fowler, who, with his partner, Benjamin Baker, had built bridges across the Severn estuary (which divides the west of England from south Wales). These highly qualified engineers believed a bridge at the Forth could be done. With no time to lose, financial and legal steps were taken, and the Abandonment Bill was withdrawn before it could finally pass and become law.

Work on the previous bridge had ended in January 1881 and Fowler and Baker laid a new plan before railway companies less than nine months later. It took only two hours for the companies to accept their proposals, and work began on preparing a new Parliamentary Bill. That Bill passed easily because the engineers were highly regarded and government inspectors validated their plans. The Bill went through all its stages and was given Royal Assent on 12th July, 1882. At last there was a realistic design.

Attrib: Wilhelm Westhofen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attrib: Lock & Whitfield (?)., CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

But there was still widespread fear whether any bridge over the Forth could be safe. Therefore approval came with many stipulations about its strength, and included rules requiring inspection of construction work by the Board of Trade four times a year. The completed bridge had to be secure, but the incomplete structure must be equally secure at every stage. Parliament specified that this must be the biggest, strongest and stiffest bridge in the world. It must have maximum rigidity downwards under the weight of trains and sideways to withstand wind pressure. Only the best of materials should be used. In addition, the Admiralty required that a bridge must not restrict shipping (the Rosyth naval dockyard lies only a short distance upstream). Murray, in his book The Forth Railway Bridge, writes: ‘The concern and caution of the engineers, combined with these restrictions resulted in the finished installation being at least twice as secure as it needed to be’.[2] (As I wrote before, I’m happy to acknowledge the help Murray’s book has been in providing detail not available elsewhere.)

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In the end three men were crucial for the design and construction of the Forth Bridge. The two designers have already been mentioned: Benjamin Baker, the designer, and John Fowler, the consulting engineer. The third would be responsible for actually building the bridge. His name was William Arrol, a construction engineer. His business base was only 40 miles away in Glasgow.[3] All three of these men were knighted shortly after the Forth Bridge opened.[4]

Attrib: Wilhelm Westhofen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The design Fowler and Baker presented was for a three tower cantilever-truss bridge. More on what those terms mean next time. As well as drawings, they presented a 13 foot (almost 4 metre) model of the bridge to Parliament. All those who found construction drawings hard to follow – the vast majority – were entranced by the model. It was soon put on show to the public.

Today, since the Forth Bridge has stood strong for more than 130 years, it seems strange that opinion was divided on whether this bridge would last. Even the Astronomer Royal wrote to The Times newspaper asserting a gale less than had blown down the Tay Bridge might destroy this Forth Bridge. Spectators stood in lines to see the bridge model, and Fowler and Baker were constantly interviewed about its safety.

Finally Fowler and Baker had a photo taken to illustrate the stability of a cantilever design. Two men (many suppose they were Fowler and Baker themselves) sat on chairs, with arms extended supporting a plank on which sat Kaichi Watanabe, a Japanese apprentice of the firm. Behind them was an illustration of the bridge. As well as their arms they used broomsticks. The men represented the bridge towers, and piles of bricks represented the far ends of the bridge. Kaichi’s weight created compression, with every part of the arrangement supporting the rest. It was all stable.[5] Fowler and Baker were not just engineering experts but superb publicists. The photograph was published in newspapers around the world, convincing many about the bridge’s stability. The photo still features on postcards today.

I’ll stop here. The design work is done and approved, and the next blog will cover the remarkable story of the bridge’s construction.

Before finishing, three things have stood out for me from what’s been covered this time.

First, because someone is sure they’re right doesn’t prove they are. I have some sympathy for Thomas Bouch. He was a visionary who never stopped trying. But I suspect he was also too great a salesman, persuading people his ideas were sound when, very possibly, they had doubts. Did they really believe a bridge resting on mud was a great idea? I suspect not. Corrupt finances halted that plan but Bouch returned later with a different design. Why not the original? Might he have always been uncertain about a bridge resting on a bed of mud? Yet he’d persuaded everyone to let him build it just seven years earlier. A great salesman can sell a bad idea. Wisdom lies in recognising what’s bad and refusing it.

Second, the futures we envisage can suddenly change. Bouch had a bridge complete and operating over the Tay, and another just beginning across the Forth. Surely disappointments were all in the past? Then the Tay Bridge collapsed, he was discredited and all he had done and all he might one day do was changed. He never recovered. For others – especially Fowler, Baker and Arrol – the day of opportunity suddenly dawned, and their names have gone down in bridge-building history for their work on the Forth Bridge. There’s no place for either uncertain optimism or uncertain pessimism about the future.

Third, getting the brilliant best pays off in the long-run. The Forth Bridge met all the conditions laid down for it. It’s a marvel of design and construction. Recent inspections have shown it’s still in excellent condition. I’ve detailed many earlier attempts to bridge the Firth of Forth. None were built. The best was worth waiting for, the Forth Bridge.

Lastly, there are points I raised last week which are not yet addressed:

- The surprising reason so many construction workers died.

- When painters reached the bridge end, they began painting again at the beginning – true or false?

We’ll get to those. But here’s one more:

- How did men work under water (without diving suits of any kind) building the piers on which the bridge rests?

I’m learning a lot, and I hope you are too. More to come.

[1] The official report can be found at: https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/documents/BoT_TayInquiry1880.pdf The extracts quoted are from pages 41, 44.

[2] Murray, A. (1983/1988) The Forth Railway Bridge A Celebration, Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh.

[3] Arrol’s business was eventually called Sir William Arrol & Co., and among its many other major construction projects are these: the replacement Tay Rail Bridge (1887), Tower Bridge in London (1894), Forth Road Bridge (1964), Severn Bridge (1966).

[4] Further fascinating information about these three men can be found here: https://www.theforthbridges.org/forth-bridge/history/the-bridge-builders

[5] Knowing little about engineering, I may have explained Fowler and Baker’s illustration poorly. It was, thankfully, sufficiently convincing to the public of their day.