A tourist was told he must see the Forth Bridge. ‘Of course,’ he replies, ‘but where are the other three bridges?’ That’s an old joke which rests on the tourist only hearing the bridge name and not knowing the spelling is Forth, not fourth, or that the bridge in question is over the Firth of Forth[1] in east central Scotland near Edinburgh.

The Forth Bridge is only 30 miles from where I grew up. I was young when my parents took me almost underneath the bridge, down by the river where the ferry took car and foot passengers from North Queensferry across to South Queensferry. I hardly remember the ferry, but the memory has remained of the giant bridge towering over me, carrying trains high in the sky.

When I refer to the Forth Bridge, I’m using its proper name. But for some 60 years it has been commonly referred to as the Forth Rail Bridge to distinguish it from the nearby Forth Road Bridge and from the recently constructed Queensferry Crossing, a second road bridge. All three bridges impress me, but it’s the Victorian-era rail bridge that has always taken my breath away.

I’m hoping my excitement and fascination about that bridge is contagious. At the end of October 2021 I wrote a blog about the Tay Bridge and its disastrous collapse during a storm. Around 75 lives were lost. (You’ll find it here: https://occasionallywise.com/2021/10/). Many people have read that blog, including a surprising number in America. I hope this bridge story also captures interest. There’s no collapse to describe though, tragically, more died building the Forth Bridge than were lost when the Tay Bridge fell into the river.

The Tay Bridge and Forth Bridge both straddle estuaries, and they have a shared geographic connection. The Tay Bridge goes north from the county of Fife towards Dundee and the Forth Bridge goes south towards Edinburgh. As a Fifer, I like the idea that my county is at the centre.

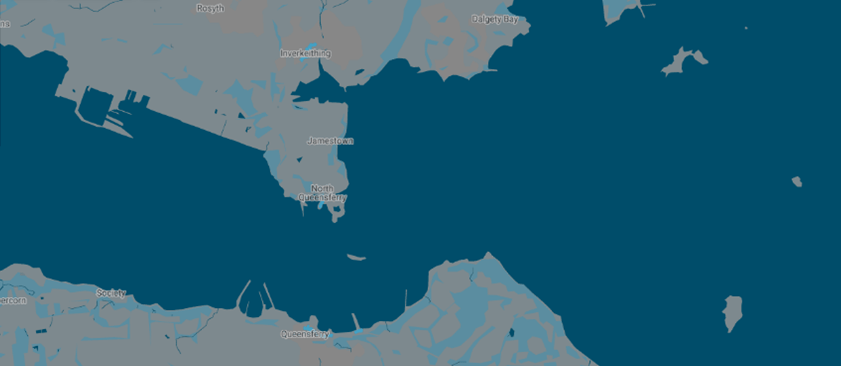

The Forth Bridge stands where it does because it almost couldn’t have been anywhere else. The maps explain. The first one shows east central Scotland. Fife is the county in the middle – it looks like a Scottie Dog facing right. At the top of Fife lies the estuary of the River Tay. The Tay Bridge was constructed where the river narrows just south of Dundee.

Look to the southern edge of Fife and you see the much wider estuary of the Forth with Edinburgh just below it. What train companies wanted was an uninterrupted route north passing through Edinburgh and Dundee. Where could a bridge be constructed over the Forth? Most of the eastern part of the estuary was too wide. To the west the river narrows the further you go upstream, but building a bridge there would be a major diversion from a straight route up the east coast of Scotland. There was just one place near the mouth of the Firth where the land to the south and north jutted out, exactly where the two Queensferry villages were located.

That point is the focus of the close-up map below. The river narrows just south of Dunfermline and Inverkeithing, which is why most ferries crossed there. That part of the river had another advantage – a small island halfway across. It’s hard to make out, but an outcrop of rock pokes its head just above the water at the midpoint. That’s Inchgarvie Island which will be a significant secure base for the central tower of the Forth Bridge.

But, our story begins not just hundreds but thousands of years earlier. In this blog I’ll focus on events before the Forth Bridge was even designed.

As we begin, let me commend Anthony Murray’s book The Forth Railway Bridge,[2] one of the most valuable sources of information for me. (I suspect the book is out of print, but there are second hand copies for sale.)

The era of boats

The first crossings of the Firth of Forth happened in ancient times before history was recorded. Small boats are fragile, and the Forth estuary was no stranger to strong tides and fierce winds, so those voyages were hazardous. Yet, the people who lived by the sea or large rivers weren’t fools. They knew when to cross.

Ferry crossings also began millennia ago. Ferries would be slightly larger vessels, likely capable of carrying several people plus cows and horses. They increased in importance when Dunfermline, located just north of the river, became the ancient Scottish capital. Margaret, an English princess, married King Malcolm III of Scotland in 1070. Queen Margaret (later Saint Margaret) was a pious Christian and apparently a good influence on her husband. She became noted for her charitable works, and part of her charity was to properly establish a ferry across the Firth of Forth so pilgrims could travel more easily to St Andrews (in the north east of Fife). The ferry became known as the Queens Ferry and the villages between which the ferry crossed were called North Queensferry and South Queensferry. Some 820 years later those two places would mark the ‘ends’ of the Forth Bridge.

One of Margaret’s sons, King David I, put the ferry crossing on a sounder footing, and granted oversight of it to monks in Dunfermline. During medieval times the ferry was a profitable enterprise. In 1589 James VI (later James I of England) gave the ferry rights to his bride as a wedding present. Early in the 1600s, the ferry passage was divided between 16 feudal superiors. They didn’t operate the ferries, but raked in their share of considerable profits.

The ferrymen appear to have been rough characters, seeing off rivals trying to steal business, lacking civility to customers, and having punch-ups among themselves. In 1637 two ferrymen were fined five pounds each for fighting. That was a substantial fine but each had to pay his five pounds fine to the other, so neither won nor lost. What may have bothered the men more was an order that required them to be friends and drink together.

An oddity for us, but not for those times, was that ferry fares were charged according to the status of the passenger, ranging from three shillings and four pence for a duke, earl or viscount, down to one penny for a humble man or woman. Ordinary folk were cheaper than some animals. A horse, cow, or ox was two pennies, but 20 sheep just four pennies. Everyone and everything had its value, with a simple citizen half the price of a cow. Clearly a boatload of aristocracy was the ferryman’s dream cargo.

The ferry service was much criticised: ferries not in good condition; landing places inconvenient and dangerous; piers scarce; services irregular, and impossible when wind and tide unfavourable; no oversight of the system; ferrymen unpleasant. It was also difficult to access the shores to catch a ferry – transport was bad on the Edinburgh side and nearly non-existent on the Fife side. No airport buses departing every 15 minutes in those days.

Despite the problems, by the early 19th century ferry traffic was increasing. That stirred a demand for change. So a Board of Trustees was set up to consider what could be done. It reported that the private individuals running the ferries were not likely to take account of public convenience to the extent now required, and recommended nationalising the ferry service. The proposal was fiercely resisted by those who owned the ferries – they called it ‘a violent invasion of private property’ – but the Bill to nationalise the service was passed in 1809.

New ways to cross the river

The increased traffic, and inadequacy of the ferries, stirred ideas for other ways to cross the Forth. This was the early 1800s, close to the Age of Enlightenment, and several more-or-less enlightened ideas were put forward.

One radical proposal came from a group of Edinburgh engineers – they would tunnel under the river. They knew of a London tunnel project under the Thames, and of a mining tunnel under the Firth of Forth at Bo-ness (about 10 miles upstream) which had gone a mile out under the river without difficulty. Led by John Grieve, three engineers surveyed the bed of the Forth at Queensferry and concluded a tunnel was very possible.

But there were challenges other tunnel projects had not faced: the great depth of the water between North and South Queensferry, and the type of rock under the river bed. Both of these factors would make tunnelling difficult. They were forced to modify the route the tunnel would take, but that meant the southerly entrance would be close to Hopetoun House, considered one of Scotland’s finest stately homes with 6,500 acres of grounds. The owner, the Earl of Hopetoun, strongly objected. Grieve pressed on as best he could and drew up plans for a £160,000 project:

- It would take four years to construct

- There would be two separate tunnels, described by Grieve as ‘one for comers; one for goers’

- Each passage would be 15 feet high and 15 feet wide (15 ft = approx 4.5 metres)

- There would be a raised sidewalk for pedestrians

Grieve issued a prospectus and shares were offered at £100 each. It got little interest. He tried again the following year, but with no greater success. The scheme collapsed. Grieve was disappointed. The Earl of Hopetoun was delighted.

A quick aside: the idea of a tunnel under the Firth of Forth was revived in 1955. A Forth Road Bridge Joint Board had been set up to plan and oversee the building of a road bridge. But first the Board considered drilling a tunnel under the estuary close to the rail bridge. But, like Grieve’s proposal, after research the idea was abandoned as being too ambitious and too expensive.

Back to our main story. Between 1808 and 1817 new piers were built on both shores. These were ramped piers (sloping down into the water), allowing ferries to dock whether the tide was high or low. They were so well constructed they handled ferry traffic until 1964. It stopped then only because the Forth Road Bridge was opened, and the ferries were consigned to history.

New piers made a big difference to the ferry service, but ferries could never satisfy 19th century transport needs. This was an era of growth and innovation. Engineering flourished, new roads were built, and bridges constructed where previously they were thought impossible. Imaginative and impressive engineering projects were being developed across Scotland, and all around the world.

An Edinburgh civil engineer, John Anderson, was excited by giant wooden bridges built in China. One bridge was reported to be three miles long. Anderson’s idea was not for a wooden bridge across the Forth, but a suspension bridge so extraordinary it would be one of the wonders of the world. His favoured site was where the ferries crossed. That was the most obvious location, partly because the river at that point was narrow, and because of the small island, Inchgarvie (as explained earlier) The name Inchgarvie is Gaelic and means ‘rough island’. That’s what it is, a small island of solid rock. However, it’s not as modest as it appears, because (like an iceberg) it’s bigger below sea level than above it. Inchgarvie was barren rock but perfect for supporting the centre of a large bridge. The pillars and columns of Anderson’s bridge would be made of cast iron, and coated in linseed oil when hot to ward off rusting. The roadway would be sufficiently wide to allow two-way traffic plus pedestrians. It would be suspended by chains either 90 or 110 feet above sea level, and could be no lower as ships with tall masts had to pass underneath.

Anderson wanted his bridge to be a thing of great artistic merit. He wanted it to look very light so he would use as little iron as possible to reduce the bridge’s weight and mass. With dry humour one later writer said the bridge would indeed have looked very light and slender, almost invisible on a dull day, ‘and after a severe gale it might been no longer seen, even on a clear day’. Anderson’s imaginative but unrealistic design won no support and the plan for a near invisible bridge became exactly that: invisible.

Other developments during the 19th century were significant for the eventual construction of the Forth Bridge.

Travel by train. The first purpose built railway, a line between Liverpool and Manchester, was authorised in 1826 and opened in 1830. It was a success from the start, beating other forms of transport on time and cost. Road transport was slow and expensive. Canals were used between Liverpool and Manchester but the journey time by rail was one and three quarter hours compared to 20 hours by canal, and the charge for carriage by rail was half the cost of carriage by canal barge. From the start trains were used by the Post Office and soon after for newspaper circulation around the country.

The expansion of railways lines was fast. In 1836, 378 miles of track were open. Eight years later that number had risen to 2210 miles and soon many more. Railways changed society. People moved out of cities because they could now commute to work. Seaside resorts were developed because they could now be reached. Businesses sent their goods throughout the nation, because transport was affordable and fast. In today’s jargon, trains were a breakthrough or disruptive technology.

Because of these economic and convenience benefits of rail travel, it was no longer realistic to think a bridge over the Firth of Forth should be designed for horses, carts and pedestrians. It must carry trains.

Oddly, though, before any bridge was built trains were already crossing the Forth estuary. They floated over.

In 1849 a young man called Thomas Bouch was appointed manager and chief engineer of the Edinburgh and Northern railway and tasked with developing travel up the east coast of Scotland. But Bouch faced two immense problems – the wide estuaries of the Tay and Forth rivers. To make a lengthy journey north or south you could take a train close to an estuary shore. Then goods and people had to detrain, board a ferry, travel through Fife by road or train, get on another ferry, and finally board another train to complete the journey. East coast travel could never prosper while those difficulties existed.

Bouch’s ambition was to build bridges, but he needed a quick fix. His initial solution for crossing the Firth of Forth was what he called a ‘floating railway’ – steam ships big enough and strong enough to carry a train. His first ferry was named ‘Leviathan’, which had proved its seaworthiness because it was built in shipyards on Scotland’s west coast, then sailed north, across the top of Scotland where wind and waves were anything but friendly, and back down the east coast to the Firth of Forth.[3]

Bouch had wasted no time. Within two years of his appointment, his train-carrying ferries began. There were already rail lines running to Granton, near Edinburgh, on the south coast of the Forth, and from Burntisland in Fife on the north coast, so the train-carrying ferries sailed between those two places. It worked, and the floating railway operated for several decades.

But Bouch’s ferries could not be a long-term solution. They had limited capacity, limited frequency, and limited convenience. The demand was for rapid and comfortable train transport, and the answer did not lie with ferries.

A bridge had to be built. And at exactly that time another major development made a large, strong bridge over the Forth a better prospect than ever before.

Reliable steel. Well into the 19th century, iron dominated the building world. It came in two forms:

- Wrought iron – wrought is a past participle of work, so wrought iron is ‘worked iron’

- Cast iron – iron shaped by a casting process.

Each has advantages and disadvantages.

Wrought iron is pliable when heated and reheated, so can be bent into any desired shape. It gets stronger the more it’s worked, is not prone to fatigue, and can suffer a lot of deformation before it fails. It’s been used since about 2000 BC.

Cast iron is not pure iron; it contains small elements of carbon, silicon, manganese, perhaps traces of sulphur and phosphorus. The elements are heated beyond melting point, then poured into moulds which give the cast iron its shape. It’s very hard but also brittle. When stressed it’ll break before it bends.

The advantage of cast iron is suitability for complex shapes – think of the decorative metal back to a garden seat – which would take enormous time for a blacksmith to create. But, though strong, cast iron won’t bend when pressure is put on it, and may possibly collapse.

Many buildings and bridges were built with iron. But they had limits. Several bridges collapsed because their underpinnings were cast iron.

Around the mid 1850s, Sir Henry Bessemer developed manufacturing processes to create quality steel which could be used economically in construction. He intended his work to be used for weapons, but it had wider applications. The Bessemer process is described this way: it ‘involved using oxygen in air blown through molten pig iron to burn off the impurities and thus create steel’.[4] It was revolutionary.

This new steel was sufficiently strong, resilient and economic for the grandest and greatest of engineering projects. It didn’t become used widely until about 1880, but that was exactly when it was needed for the Forth Bridge.

It was now time for a serious approach to a bridge over the Forth. The ‘beginnings’ of this story are, therefore, at an end. It’s where we pause, but the story will continue in the next blog.

Already there are lessons we can learn, including these:

- During the early years there were people who believed a bridge spanning the Firth of Forth could never be built. They were wrong.

- The first bridge concepts were too small and too fragile to meet the need, although understandable given the technology of the time.

- New developments created a need and an opportunity. The creation and expansion of train services were the need. The upgrading of steel to major construction quality was the opportunity.

- Eventually the time came to act. An age had dawned which demanded bold innovators. Those innovators emerged, and their work was and is magnificent. After more than 130 years the Forth Bridge still fulfils its purpose perfectly.

These four points make me ask these questions. What is there I could be doing but my vision is too small? Beyond me, what are the challenges of this age that need great innovators, and a population willing to adapt, so dangers like viruses, inequality, racism, and climate change can be challenged? This is not a time for saying ‘That could never be done’. It’s the time when something must be done.

Thank you for persevering through a long blog. As the story progresses, we’ll find out:

- Was there a serious proposal for bridge supports simply to float in the river?

- A surprising reason so many construction workers died.

- Why Thomas Bouch was hired and then fired as bridge designer

- When painters reached the bridge end, they began painting again at the beginning – true or false?

And many other important and not-really-important facts. So much more to come.

———————–

[1] ‘Firth’ – often used in Scotland – can refer to a river estuary or an inlet of the sea. The Firth of Forth is both.

[2] Murray, A. (1983/1988) The Forth Railway Bridge A Celebration, Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh.

[3] Some of these details come from an obituary of Thomas Bouch following his death in October 1880.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Bessemer